On Prisons, Pardons, Puerto Rico and the WRI

Matt Meyer

Practically my very first act as an overtly political person was to challenge—then publicly defy—what seemed like an unjust U.S. law. At age 17, I declared that I would refuse to register for a military draft that might put me in Central America or elsewhere, fighting against people and ideals which I had nothing whatsoever against. Despite the potential of five years in prison, my refusal tremendously strengthened me, and it remains one of the proudest moments of my life. There is something very liberating about openly resisting what seems like an invulnerable, impenetrable power and "living to fight another day," whether behind bars or not. Edward Snowden is undoubtedly correct: any movement for progress will and must involve defiance of unjust laws and/or unjust implementation of potentially acceptable laws corrupted by unjust, oppressive empire-nations.

It was not a surprise that, at the end of his term as U.S. President, Barak Obama granted clemency to a number of incarcerated peoples. That one of those people was military resister and whistle-blower Chelsea Manning was a bit more of a shock; Manning’s case was fairly clear-cut, though strict defenders of freedom of speech joined with anti-war activists to mount a formidable campaign for the transgender former military intelligence analyst. Sentenced to 35 years’ imprisonment for violations of the Espionage Act (Manning released close to 750,000 classified or sensitive documents), Obama commuted her sentence to what will effectively be four years behind bars.

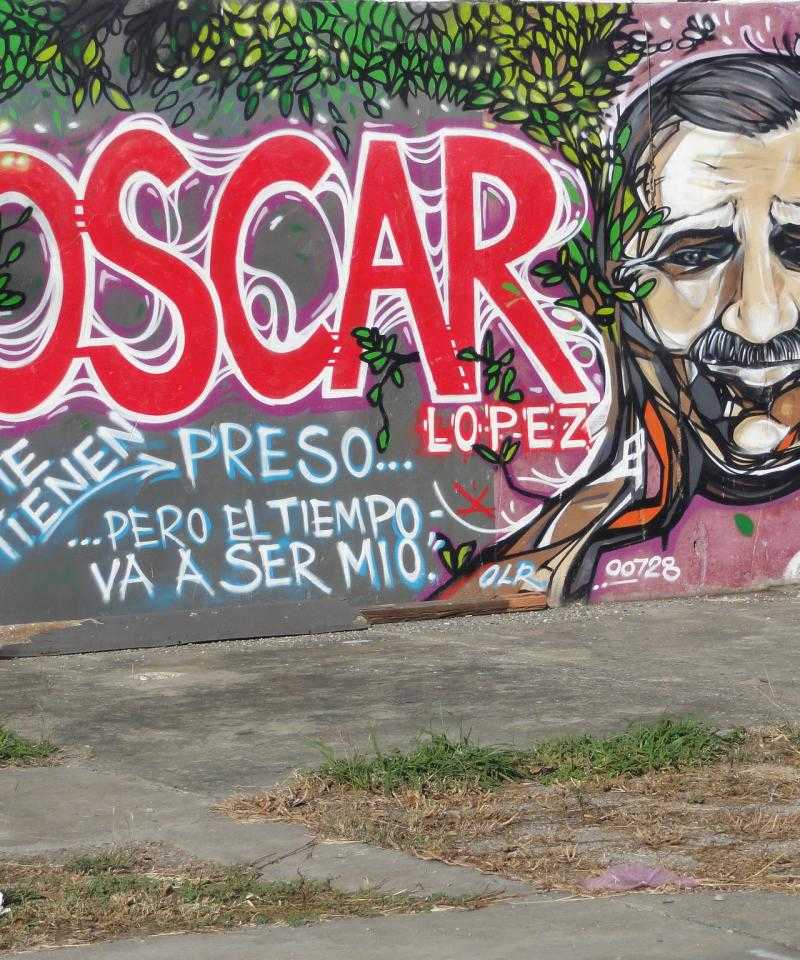

Even more surprising was the decision to release Puerto Rican political prisoner Oscar Lopez Rivera, the longest held prisoner in the history of U.S.-Latin American relations. Contrary to misinformed reports, Lopez Rivera was never convicted of any involvement in violent crime, nor did he refuse to renounce violence when President Clinton offered him and other Puerto Rican nationalists clemency in 1999. The offer Clinton made demanded that this activist—convicted only of the “thought crime” of seditious conspiracy—serve more time than his co-defendants, and left two co-defendants out of the deal. Now that all his fellow compatriots have been released, his continued imprisonment was hypocritical at best. The fact that Lopez Rivera once belonged to an organization which did take responsibility for illegal acts doesn’t make every member of the group a criminal; that’s simply not the way even the U.S. legal system works. But it was notably not on legal grounds that Obama based his commutation.

Make no mistake about it. Despite the growing involvement of a deeply religious support component from all major faith traditions joining the campaign to free Oscar, despite the insider’s influence pressing Obama for a full pardon - Oscar Lopez Rivera’s release is based on “our” strategic work. The victory of January 17, 2017—of the granting of clemency for the man still designated by mainstream media as the mastermind of the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN)—is based primarily on a consistently-held, vigorously-fought, simple but stalwart commitment to decades-long, door-to-door, community-to-community, email-to-email (or tweet to tweet) building of a massive, grassroots-based single-minded campaign.

I put the word “our” in quotes because, of course, the international campaign to free Oscar was a decades-long prospect involving scores of people, led by and especially centered in the work on the island itself. It is true that Oscar has rightfully gained the respect and support of a half dozen Nobel Peace Laureates including Archbishop Despond Tutu of South Africa, and the notice of heads of state throughout South America who have dubbed him “the Mandela of the Americas” in more than just rhetorical terms. Oscar’s centered calm and strength, his ability to weigh the personal dilemmas of continued incarceration with the political needs and desires of the majority of his Puerto Rican compatriots, has been nothing short of Mandela-like in its scope and strength. The United Nations itself, a body of almost immeasurable bureaucracy and complexity, nonetheless turned its gaze in Oscar’s direction, its Decolonization Committee pledging to visit him this year if he were not to be released. The Fellowship of Reconciliation, the American Friends Service Committee, Pax Christi International, and other related groups played vital roles. But it is also important to note the long-standing and historic role which War Resisters' International (WRI) directly played in the campaign for Oscar’s unconditional amnesty.

The Puerto Rican Committee for Human Rights was founded by renowned sociologist, educator and author Luis Nieves Falcon, who left a prestigious career to obtain a law degree and work full time as counsel to and organizer for the more than a dozen independence activists incarcerated in the early 1980s. As architect of the international amnesty campaign, Nieves Falcon, along with Oscar’s Chicago-based brother who masterminded work among the Puerto Rican Diaspora living in the U.S., developed a tight core of loyal organizers who developed various aspects of the freedom effort. From the early 1990s onward, I served as main liaison to global peace movement organizations, inter-faith religious groups, and the Nobel laureate community, and we formally launched the efforts to gain broad support within those circles at the 1994 WRI Triennial in Brazil. Over the years, many world-wide tribunals, conferences, and demonstrations were held, with WRI representatives in attendance as part of the solidarity effort. In 2002, however, shortly after twelve of the Puerto Rican political prisoners were released by President Clinton and the campaign for Oscar was gearing up, Dr. Falcon presented as plenary speaker at the WRI Triennial in Dublin, Ireland.

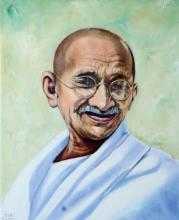

When we consider who “fits in” to the definition of “prisoners of conscience” or prisoners for peace, it is sometimes difficult to navigate the tactical spectrum of where an individual’s heart or head might lead. At the WRI India conference of 2010, for example, a petition with Oscar's fine oil painting of Mohandas Gandhi was passed around, and signed by most participants. Spotlighting Gandhi might not have been a choice for Oscar when first arrested in 1981, but his knowledge of and respect for the Indian independence leader developed over time. Oscar's daughter and one of the key spokespeople for the campaign, Clarissa Lopez, was an active participant of WRI’s 2014 South Africa conference, where—among other things—she was able to meet Archbishop Tutu and thank him for his consistent support (originally solicited during his days as chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission). Countless events, emails, letters, petitions, news articles and updates were put together by WRI members, sections, affiliates and friends, as a whole, including work at several junctures to prepare for and engage in nonviolent civil disobedience. At each point, a single letter or a signed petition, a small and solitary event or even attendance at a big conference, may not have seemed like quite enough; but in the end, we won.

From an organizing perspective, we realized that to plan for a concrete victory, we would have to think differently than the average “left” effort; we would have to analyze our particular, twenty-first century geopolitical context. We understood that such an effort would have to be deeply dialectical in nature, rooted in clear (if often-seemingly visionary and grandiose) objectives, based on strategic thinking which evolved over time due to changing material circumstances, utilizing a diversity of insider/outsider tactics. In addition, the granting of clemency to one man after 35 years behind bars is, in itself, a mildly reformist act; we knew that the Oscar case had more far-reaching implications as Oscar the man became the definitive symbol and champion voice of an entire people. More than any Puerto Rican, he personifies a special unity which values cultural integrity, justice for all, grassroots participatory democracy, and the power of love.

As a movement, we are well aware that there will likely be future U.S. political prisoners. From an internationalist perspective, we know that repression breeds resistance and that the oppression of the current period will make rebellion inevitable. With the struggles of the 1960's and 70's fading into history, however, freedom for the iconic elders of this period who are still behind bars must be made a priority of every human rights and peace organization. If we are to build peaceful, democratic, and just societies, we know that prison should never be a place for any peacemakers or justice-seekers. Let us work in better coordination and unity to meet these trying times, and build consciousness throughout the world, as we break both the literal and figurative prison chains around us.

Matt Meyer serves as War Resisters’ International Africa Support Network coordinator, and is a Council member and United Nations representative of the International Peace Research Association. A past Chair of the War Resisters League, he is a senior consultant affiliated with both the University of Massachusetts/Amherst Resistance Studies Initiative, and with the University of KwaZulu/Natal’s Centre for Civil Society.

Add new comment