Conscientious Objection in History

Return to Conscientious Objection: A Practical Companion for Movements

Hannah Brock works in the War Resisters' International office on the Right to Refuse to Kill programme, working with conscientious objector movements, anti-conscription campaigners, and those challenging the militarisation of youth. She has also been involved with grassroots nonviolent movements in the UK and Palestine. Here, she gives us an overview of conscientious objection in history and who have been conscientious objectors.

Being forced to join a military group is not new. For millennia, enslaved and bonded peoples – usually men – have been compelled to leave their homes and risk their lives in defence of their masters' or their monarch's wealth and power. Much more common, however, have been powers and principalities relying on 'professional' or mercenary armies to wage their wars.

The process of conscription – compulsory mass enlistment, mostly of men only, into to the armed forces of a nation state – is usually traced to France after the 1793 revolution. Just prior to this in North America, conscription or 'the draft' had also been enacted by Washington during the 1775–1783 'War of Independence'. Conscription in this and the century that followed would become an important process in the identity building and creation of nation states, as well as a product of them especially in Europe. At this point, Suadi Aydın argues, a nation 'in its entirety' became the actor of war.1

Rejection of the idea of personally having to join the military, and opposition to armed violence for everyone, goes back much further. Maximilianus is recorded as an early 'conscientious objector', for refusing to join the Roman army when they came looking for soldiers to swell their ranks in Numidia (today's Algeria) in 295 CE. He said that as a Christian he could not use violence and he was executed.

Religious grounds for conscientious objection, such as Maximilianus', were often the most visible in the early history of conscientious objection, and it was to religious conscientious objectors that modern rights of exemption from conscription were first granted, for example in Holland for Anabaptists and Quakers in the 16th Century. However another stream of influence for antimilitarists and War Resisters' International (WRI) is the history of draft resistance, evasion, and desertion within the military. Sometimes less organised, such resistance is often less visible and therefore less recorded, with notable exceptions like opposition to the Vietnam war from US draft evaders in the 1960s.

In Egypt, when conscription was introduced under Muhammad Ali in the early 1800s, many people injured themselves hoping they would be declared unfit for military service. Many had limbs amputated, were blinded in one eye, pulled out their own teeth (teeth being crucial in tearing open shot packets), or removed a finger (so as to become unable to fire a rifle). Instead, the army set up a corps for disabled musketeers. Many also fled, primarily to Syria. For WRI, you could say that the individual conscience and unarmed collective refusal come together to influence conscientious objection as an antimilitarist tactic. Resistance to conscription has also prompted armed revolt, including in Palestine in 1834, when Muhammad Ali's taxation and conscription triggered what's known as the Peasants' Revolt.

Much of the history of conscientious objection that is well known and historically recorded in the 18th and 19th Centuries relates to Europe and religious European émigrés – for example in north America – and is associated especially with often persecuted groups like Jehovah's Witnesses, Quakers, Mennonites, Brethren and other Anabaptist groups. Their rejection of state laws, such as conscription, was often one explicit motivation cited by those who persecuted them. These groups offered organisation and internal solidarity. Such mechanisms are necessary when taking action which is firstly unusual, secondly illegal, and thirdly often deeply unpopular. The resistance of other non-religious groups, and across the world beyond Europe in this period, is often less well recorded and celebrated – particularly if we take a broad view of CO, as this book does. This does not mean that such resistance did not exist, just that many historical and pacifist explorations from majority European groups (as WRI was in its foundation) were ignorant of them, and so have not helped maintain their legacy as living history. This chapter cannot help but be a product of what has been well remembered in books, personal and institutional memory of pacifist groups, and therefore may suffer from the limitations of this 'known' history.

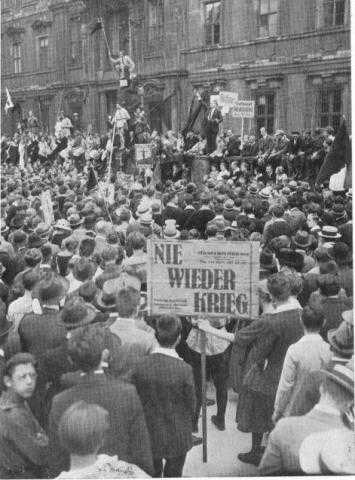

WRI was founded in 1921 in Bilthoven in the Netherlands by European conscientious objectors who had lived through the 1914-18 war. They arose chiefly from humanist, socialist and anarchist movements as well as some from religious movements (many Christians were instead part of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation [IFOR], founded in 1919, also in Bilthoven).2

The pacifists and antimilitarists active in these movements were struggling against conscription as a whole and 'total war' – the 'absolute mobilization of all technical and human resources'3 that occurred at the turn of the twentieth century more generally, whilst many of the religious objectors previously had been concerned with campaigning for their own exemption primarily from conscription – though this does not apply to all. This struggle against total war was articulated memorably in Dutch anarchist and antimilitarist Bart de Ligt's 1934 'Plan for Struggle against War and War Preparation', of which conscientious objection was one of what Bröckling calls an 'encyclopaedic' list of tactics against militarism.

Recognition of conscientious objection as a right was also recognised increasingly from the early 20th Century onwards – though only in a very few states, firstly in Protestant Europe. In Norway, protection of conscientious objection rights became law in 1900, Denmark in 1917, and the British government's conscription law of 1916 was the first to allow for conscientious objection at the moment of conscription's introduction, though many conscientious objectors still went to prison in Britain during the 1914-18 war. Conscription there was a deeply controversial measure – the first introduction of forced enlistment in Britain – and provision for conscientious objectors was therefore seen as a necessary concession.4.

After the 1914-18 war, cooperation at first among European movements, and later in the century with movements across Latin and north America, Africa and elsewhere, was fostered by networks like WRI and IFOR, including at regional levels, like the International Conscientious Objectors' Meetings, the European Bureau for Conscientious Objection and by the 1990s ELOC (the Encuentro Latinoamericano de Objecion de Conciencia, later CLAOC: Coordinadora Latinoamericana de Antimilitarismo y Objeción de Conciencia, the Latin American Coordination for Antimilitarism and Conscientious Objection). Cross border solidarity was also a key part of some of the more prominent refusal movements of the 20th Century, such as conscientious objectors in the USA in the wars on Korea and Vietnam. Many objectors fled to Canada, for example, and found support there initially at a grassroots level and latterly from the government.

In Latin America, an emergence of antimilitarist movements occurred in the 1990s, sometimes in places affected by civil war – Colombia, El Salvador – and elsewhere as military dictatorships were coming to an end – in Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, etc. Young people in societies that had been so deeply impacted by these dictatorships, with their militarism and repression, found conscientious objection as a way to 'express their political awareness and developing identities, with new sets of values, distancing themselves from violence and arms struggles'.5 Rafael Uzcategui writes in the next section of this book that these movements developed with three main tendencies: religious initiatives, including SERPAJ [the peace and justice service], active in Colombia, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina and elsewhere; Marxist and anti-imperialist groups using anti-conscription campaigning as a tactic; and anarchist groups. In that context, the three tendencies did not much collaborate – as Rafa puts it: 'antimilitarism as an identity has never had its own development, separate from the three tendencies described'.

Often, campaigning for conscientious objection has taken the form of pressing for legal recognition on a national basis. Where this has been granted, there are many occasions when it has first been granted as an exemption on certain religious grounds, which is a discrimination against all other conscientious objectors. Since the foundation of international bodies such as the League of Nations and later the United Nations, many have also been campaigning for international recognition as a way of pressuring nation states. The Human Rights Commission of the UN first formally recognised the right to conscientious objection on 10th March 1987, and appealed to states to implement it. Continued efforts before and since have demanded recognition of CO, and provision for it, at various international levels as well as at regional level.

In many countries, concentrated but not exclusively in Europe, conscientious objection and anti-conscription movements have seen 'success': being part of the process that forced the end or suspension of conscription (for example in the last 20 years in Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden, Morocco, Peru and Argentina). There are some clear examples here of antimilitarism breaking down conscription – we can name Insummisión in Spain and Serbia for example. The end of conscription results in a vastly different atmosphere in which for antimilitarist groups to work, but it's not as simple as just a 'win'. Ending conscription has in many cases become expedient for a defence strategy where 'Lean and mobile armies with well trained soldiers were needed.... The large conscription armies became a relic of the past'.6 Moreover, ending conscription means one of the main streams for bringing people into conscientious objection and antimilitarist movements ends. What happens for conscientious objection movements when conscription ends is discussed further in chapter 20.

In any case, conscription does still affect millions around the world today. Conscientious objectors are still imprisoned, punished, and ill treated in many countries throughout the world where the right is not recognised – in South Korea, Israel, Finland, Eritrea, Turkey, Cyprus, and Azerbaijan, to name but a few. So the journey to conscientious objection recognition is by no means complete, nor is it – for antimilitarists – the real aim anyway.

Who have been conscientious objectors?

The history of conscientious objection is not the same as the history of war refusal in general, and is even more different from a history of those who do not go to war. What choice you make when faced with an obligation to join the military is to do with what options you have open to you. In many contexts, it's been said that the middle class become conscientious objectors, while the poor evade the draft. This is by no means true at all times and in all places, but there are many reasons why this might be the case in some circumstances. For example, where a state that does provide some kind of substitute service to the military uses a 'conscience committee' to judge the 'validity' of a CO's application: this is a potentially very daunting experience, more attractive to the more highly educated who are used to debating, having to speak in public, and so forth – aside from the political choices to be made around whether to accept such a test of one's own conscience. In today's campaigning culture where being a conscientious objector can often involve giving a lot of media interviews, this could also be deeply intimidating, depending on your aptitude, background and experience. Does it lend itself more to middle and upper class people? (see Noam Gur's interview, chapter 6).

Things are also much more complex than a working class/ middle class dichotomy, however. How do you evade the draft? Do you flee abroad, go underground, continue to study, work in a 'reserved' profession whose workers do not get called up? Ability to take such action relates to privilege and status in different ways. The reverse is also true: by no means all conscientious objection movements have been devoid of working class participation and leadership.

Because it's mostly men who are called to war by the state, it's mostly men who are conscientious objectors to military service. This is not the case everywhere: today, women are conscripted in Eritrea, Israel, Mozambique and Norway. In Israel, one of the largest conscientious objection groups is a feminist group – New Profile – with many women members. But conscientious objection movements historically have been male dominated, and it takes decisive effort to ensure that their work not only – at the absolute least – includes women in a meaningful not-just-making-the-sandwiches type way, but also recognises the ways patriarchy and militarism relate.

Women have also organised separately using conscientious objection as a tool, declaring themselves objectors to militarism in their own lives – for example in Turkey (see chapters 23 and 24). WRI's 2010 book Women and Conscientious Objection – An Anthology goes into much more detail on this. In this volume however, see chapter 24 for some examples of ways of both including patriarchy in an understanding of militarism and power, and chapters 7 and 27 for ways of ensuring that this understanding translates into organising differently.

Books about conscientious objection and its history will talk about pacifists, religious adherents and activists working from 'conviction politics', who organise campaigns together. Just as important, you could argue, is opposition on what you might term 'personal' grounds: 'I have a family to feed, food to grow, elders to look after – I cannot just leave my home and join the army'. Or, 'I do not want to die'. These aversions to enlistment are just as relevant to anti-conscription campaigns as political convictions. Firstly because they represent compelling arguments about the importance of personal liberty and power over our own lives; secondly because they are widespread; and thirdly because they highlight the inherent horrors of war and life in an itinerant, hierarchical killing force – i.e. the military – in a less abstract way than many ideological arguments. But such opposition is harder to harness than a shared ideological commitment between people who might be organising together anyway, such as left wing groups. Moreover, it might not seem as 'worthy' to the states they are trying to challenge, and could therefore be less likely to provoke sympathy among opponents or command respect from the military they are trying to evade.

If the history of conscientious objection has been originally religious, overwhelmingly male, and often the choice of those from more privileged backgrounds, what has conscientious objection to offer women, people of colour, and antimilitarists from the majority or 'third' world? We hope this book answers some of these questions with examples of feminist movements as well as anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist campaigners from the majority world. But it is also our hope that some of its contents are a challenge to movements who might be male dominated, or white dominated, or middle class dominated. This is not because the authors of this book, or WRI and its network, do not suffer from being male dominated, or white dominated, or middle class dominated. At times we have and we do. We do not have all the answers, but we wish to engage with the questions. We also recognise that whilst conscientious objection is an important tool against militarism, it is only one, and other tools might at different times and places offer a more radical alternative to the trappings of militarism like heroism, sacrifice and hierarchy.

And what of the future? Conscientious objection movements have often been inspired by the old expression 'imagine if there was a war and no one showed up?' Well, soon perhaps hardly anyone will need to 'show up' for there to be a war, as technology advances and can do the killing of 1000 armed people at the touch of a button. Conscientious objection movements are especially threatening to militarist states when acting as a challenge to the kind of 'total war' mobilisations of the so called 'world wars' of the 20th Century. As increasingly professional armies, and robots, take over from the 'boots on the ground' mentality that needs men, and men in their droves, to act as soldiers, we will have to be inventive and flexible in how conscientious objection is used. We do that best together, and that's one of the reasons WRI exists and pacifists around the world continue to invest in cross border communication through organisations including WRI.

1. Çinar, Özgür H. and Üsterci, Coskun (eds.) 2009, Conscientious Objection: Resisting Militarized Society, (London and New York: Zed Books)

2. This is not a coincidence! But rather testament to the role played by Kees and Betty Boeke, in whose house both WRI and IFOR were founded. Service Civil International was also founded there.

3. Bröckling in Çınar, p. 55.

4. The whole island of Ireland, then part of the United Kingdom, was exempted from conscription, for fear of a popular revolt. (cf. Çınar, p. 22).

5. A quote from Javier Gárate, who founded Chile's Ni Casco Ni Uniforme conscientious objection group; correspondence with the author.

6. Lammerant, Hans 2013, 'The end of conscription and the transformation of war', in The Broken Rifle [online] May, <http://www.wri-irg.org/node/21760>, accessed 12th June 2015.

Add new comment