The relation between militarisation and extractive industries. A view from Latin America.

Lexys Rendón

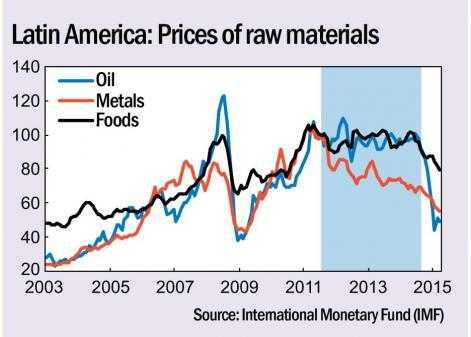

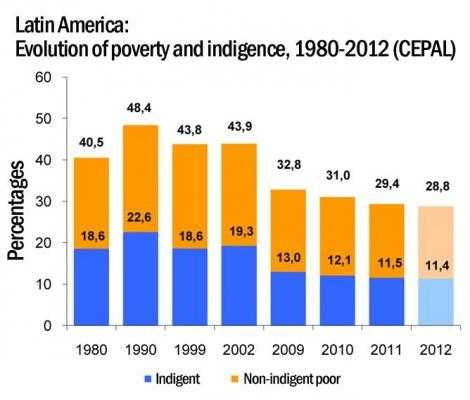

Between 2003 and 2013 - while the rest of the world experienced a wave of economic crises - Latin America showed good economic indicators. The continent benefited from the “boom of price in raw materials”; historically, the region's main export products are energy resources like oil, gas, coal and other minerals, and this continues today. In 2011, for example, 13 of the 20 biggest companies in Latin America belonged to the oil, gas, mining and iron and steel sectors. The money that entered the region managed to reduce poverty; in 2012, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) affirmed that the continent showed the lowest percentage of poverty (28.8% of total population) in the last 30 years.

However, the high economic incomes were not only destined to reduce levels of extreme poverty, they were also intended to modernise the armed forces of Latin American countries by a significant increase in arms purchases. In a study carried out by Peace Laboratory, based on figures from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) it was revealed that Latin America had increased it's weapons purchases by 150%, spending $13.624 million between 2000 to 2010. Military spending worldwide in 2012 reached $1.7 billion, or 2.5% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In Latin America, defence spending was about 4% of its total GDP, above the world average.

In turn, there is a clear relationship between the growth of a primary economy exporter based on the intensification of extractive companies, which is supported by both "left" and "right" governments, and the increased militarisation of the territories where this takes place. On this, the researcher and Uruguayan journalist Raúl Zibechi said: “There is not extractivism without militarisation of society... This is not to be a mistake, militarisation is part of pattern. There is not surface mining, mega mining without militarism. One cannot see it in the city where you live, if you live in the city, but if it comes a little you will see an increasingly militarised environment.”

We understand “militarisation” not only as the physical presence of members of the armed forces in a determined territory, but also as the growing influence of the values of the military in society. If we qualify the period between 2003 and 2013 in Latin America as “the extractive decade”, we can say that after those 10 years the region has become much more militarised. This is clear not only in the high budgets for the operation of the armed forces and the increase in the purchase of weapons, but also in a process of criminalisation of peaceful protest of social movements, popular leaders and indigenous communities that drives it, which has become common practice in several countries. This process of criminalisation includes the reform, the creation and the current proposals of laws that establish as offences historical strategies of struggle in Latin American by popular movements, such as strikes, street closures or the use of masks or hoods by protesters. Latin American governments of different ideologies like Chile, Argentina, Venezuela and Ecuador, have adopted antiterrorism laws influenced by the reaction to the September 11th attacks in the United States, and the militaristic and Manichean vision by which the government of George W. Bush faced the collapse of the Twin Towers of New York. They declare - “preemptively” - all those who exercise acts contrary to the supreme interests of the State and the Nation as internal and external enemies.

In contrast, when the reasons for which the Latin American populations are mobilizing for their rights, we find that they are indigenous and peasant communities that are leading the protests against mega-mining projects in militarized territories. Extractivism and militarism have generated broad social resistance throughout the continent. According to the Latin American Observatory of Environmental Conflicts in Peru, during 2012 there were 184 active regional conflicts, five of them cross-border, involving 253 effected communities. Some of the main demands of the movement have to do with the land in which they live; demarcation and delivery of territories to indigenous communities, the right to be consulted before making energy extraction projects, the realization and dissemination of environmental impact studies, and the mobilization against soil contamination, water and air as a result of mining and extractive activity. Today many indigenous and peasant leaders, as well as human rights defenders, have been arrested for participating in demonstrations, and are being subjected to trials in courts that do not guarantee an independent judiciary. Some protesters have been killed by the police or military forces, and their deaths remain unpunished.

In Latin America the challenges for antimilitarists are manifold. One of them is to continue to investigate and make visible the links between extractivism as a hegemonic development model after the eclipse of neoliberalism in the region, and the militarisation of bodies and territories. These points are not always clear for activists or for society itself.

Secondly we believe that comprehensive antimilitarism - which proposes a society whose operation is based on values other than militarism - can provide a view that, from another location, perform analysis and proposals to overcome the limitations of ideological debate between the "left" and "right". These are categories we now know match, at least in the Latin American case, the cult of the army, consider 'difference' as a threat or an enemy, and the use of force and the state monopoly on the use of weapons as methods for conflict resolution.

Then there is our accumulated experience in the use of nonviolent direct action as a promoter of cultural, social and political change in society. Because the history of Latin America, and the leaders of national liberation movements that used armed struggle to challenge the different colonialisms, social movements in the region continue to refer to the guerrillas or militaristic leaders like Che Guevara or Simon Bolivar. Part of the strategy of criminalisation by states is to hinder democratic and peaceful means of protest, so that the protesters resort to violent methods, which the state can then use to make a campaign of criminalisation precisely because the "violent" nature of "terrorist" protesters, which ends up isolating and fragmenting the movement itself. Antimilitarists can and should accompany these legitimate movements, the grassroots, the struggle for land, the environment, by areas of participation and enjoyment of human rights by trying to contribute in expanding the range of possibilities for real change through nonviolence.

Ajouter un commentaire