The British Armed Forces are using Covid-19 to solve a recruitment crisis and to heal their damaged reputation

This piece was originally published by Declassified UK.

Statements by the British military since the Covid-19 crisis hit the UK show that it sees the biggest domestic crisis since World War II as an opportunity. Drawing on the army’s internal marketing strategy, the military is using the idea of “belonging” to encourage young working-class recruits into joining the armed forces.

Senior military personnel have repeatedly used the hashtags #InThisTogether and #ThisIsBelonging to promote the military’s recruitment programme. In a tweet on 2 April 2020, which was later deleted, the Royal Logistics Corp even admitted: “The Army is committed to maximising its size during the outbreak of #coronavirus.”

Lt Col Kevin Bingham from Army Recruiting and Initial Training Command’s marketing team has celebrated the recruitment figures during the Covid-19 pandemic. Interviewed in the May issue of Soldier magazine — produced by the British Army — he said: “The numbers of people we are attracting continues to rise” before noting that the military had to “change some wording to emphasise that we are still recruiting in the current climate”.

Faced with declining public trust in the UK military, which is partly the result of failed interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) has also sought to recast its damaged image by positioning itself as “a force for good” in the battle against Covid-19.

Comparisons to British military successes against Nazi Germany, and of British involvement in the Battle of the Somme, are being made with support from the mainstream media.

The strength of the British Armed Forces in 2019 was 165,000, including 133,000 regular personnel (56% of whom are in the army), and 32,500 trained personnel in the reserves. Extra troops are not needed for responding to Covid-19: The military’s current recruitment drive seeks to address a longer-term recruitment and retention problem.

The MOD told Declassified that under 6,000 reservists and military personnel have so far been deployed across Britain in the Covid-19 response.

When 99-year-old Tom Moore, a former British Army officer, became a national story after raising money for charity to help with the battle against Covid-19, the UK military wasted no time taking advantage of his popularity. “Captain Tom Moore appointed Honorary Colonel to inspire next generation of soldiers,” read the headline of an Army press release posted on 29 April 2020.

Junior Soldier Ash Greenwood, aged 16, who will join 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment, told the Army website: “In the army, you never walk alone.”

“The UK Armed Forces have not undertaken additional activity to recruit personnel during the coronavirus pandemic,” an MOD spokesperson told Declassified. “Like any large organisation, there is a constant flow of personnel through the Armed Forces, so recruitment and training must continue as normal.”

‘Great opportunity’

When Mike Baker became interim chief operating officer for the MOD during the Covid-19 crisis, he announced his appointment with the quote: “In the midst of every crisis, lies great opportunity.”

From the beginning of its involvement in the battle against Covid-19, the UK military has flagged its recruitment operations. On 19 March 2020, the government announced the formation of a Covid Support Force which placed 20,000 troops on “higher readiness” to assist in the battle against Covid-19.

On the same day, an Army statement announced that face-to-face recruitment was being paused. However, “Be reassured that the British Army is still recruiting,” the statement added. “The process will continue ‘virtually’ and we are working on a different way to run our assessments which avoids bringing together large groups of candidates.”

Later in March, the British Army put out its first Covid-19 “update” video with the hashtag #InThisTogether. A third of the update was dedicated to recruitment. The UK military also made a number of media packages showing that its recent recruits are still training during Covid-19.

The Army jobs site quickly made a “Covid-19 Frequently Asked Questions” page which is now the first option under the main advert on the application page. It states at the top, “You can still apply to the Army” and adds: “The National Recruitment Centre is still operating, and our teams will be continuing to work to support your application.” There is also a special chat box to submit a “Covid-19 question”.

An internal briefing document on the Army’s recent “This Is Belonging” recruitment campaign makes clear that it is aimed primarily at 16-to 24-year-old “C2DEs” – the lowest three social and economic groups.

The UK military has long faced a recruitment problem and in 2012, the British Army sought to transform its approach by entering into a 10-year, £495-million agreement with Capita, the UK’s biggest outsourcing company. However, it has not recruited the required number of regulars and reserves in any year since the contract began. A parliamentary report in 2019 labelled Capita’s efforts “abysmal”.

In 2019, the Army was 9% short of its target. Major General Paul Nanson, who heads Army recruitment, said the month before the Covid-19 crisis hit that it was “going to take years” to get back to the levels needed.

Labour’s then shadow defence minister Nia Griffiths said in 2018 that the UK military was in the middle of a “crisis in recruitment and retention”. In the year to November 2019, some 15,120 British soldiers reportedly quit.

Former Major James Dunning noted: “It is obvious commanders will struggle to mount a major intervention operation.” The size of Britain’s armed forces has fallen for the last nine consecutive years.

But, according to one British Army newsletter from 2019, there was reason for hope. “Clearly our key messaging is resonating with the public, but there is still much to do, and we must continue to promote the Armed Forces as a career of first choice,” it noted.

The Army recently claimed it was on course to reach its targets for recruitment for the year ending 31 March 2020. The MOD told Declassified that more than 100,000 people have applied to join the Army since April 2019, an increase of 5% over the previous year.

However, a National Audit Office report in 2018 found: “The Army must … manage the number of serving soldiers and officers it retains, and ensure a constant flow of new recruits to replace those who leave or retire from service. Unless it does so, its ability to meet operational demands and adapt to meet new threats will come under increasing strain.”

The report added that “an improving UK economy with historically low levels of unemployment; a shrinking recruitment target population that is less likely to commit to a long-term career in the Armed Forces; and a public perception that the Army is reducing in size and is non-operational, making it less attractive to join.”

‘Your Nation Needs You’

Perhaps an even bigger problem than recruitment is “retention”, or the rate at which soldiers are leaving the military before the end of their contracts. It was in this context that in early April the UK military began a new Covid-19-inspired programme to recruit back personnel who had recently left the Army.

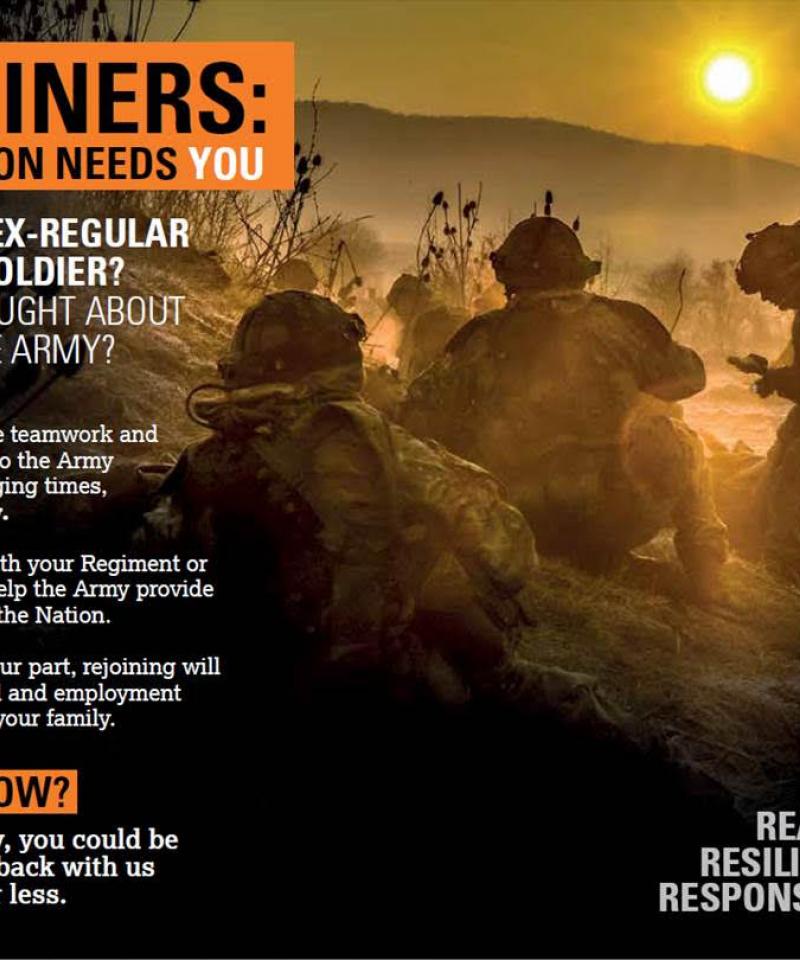

The programme is aimed at any former soldier under the age of 57, who has left in the past three years and was designated medically deployable on retirement. Those who sign up can be back in the military within four weeks. “Rejoiners: Your Nation Needs You” reads the Army’s advert for the programme, echoing the infamous Lord Kitchner recruitment advert during World War I.

The advert specifically alludes to the military’s involvement in the Covid-19 response. “Rejoin now to help the Army provide essential services to the Nation.” It then uses the instability of the economy to encourage people to rejoin, echoing the Army’s internal analysis that its target demographic for recruitment is usually “money-driven”: “Rejoin now and secure financial and employment stability for you and your family during these challenging times,” the advert advises.

As the programme was launched, Major General Matt Holmes, commander of the Royal Marines, tweeted: “‘Once a Marine, always a Marine.’ Interested in rejoining @RoyalMarines to serve your Country in time of need? Job security, good oppos and Future Commando Force ahead. Then step up once more Royal, and click this link.”

General Holmes was retweeted by TV celebrity Bear Grylls, who added a message for his 1.5 million followers: “If you’re a former Commando check this out… @RoyalMarines The Corps needs you …”

On 24 April 2020, the Royal Navy put out a press release, complete with nine photos, about Jordan Holland, who had spent eight years as a medical assistant in the Navy. She had left to become a full-time artist. “The 29-year-old decided to sign back on as medical assistant and join the collective fight against Covid-19,” the Navy wrote.

Holland also gave her own quote: “I have always and still do love the Navy. You make the best kind of friends, you work together so well, it’s a whole other world. When you leave you miss the people and the banter.” The story was regurgitated across various major UK media.

A week later, the Navy advertised for a medical assistant, claiming it’s a “career that’s packed with variety and adventure”. The tweet was marked as an advert indicating the Navy had paid to promote it. The job description was tagged “humanitarian aid” and “adventure”.

Earlier in April 2020, the Conservative MP and minister for the Armed Forces, James Heappey, tweeted his hope that former personnel would consider rejoining the military. “Hopefully people will respond not just to fight Covid but because Armed Forces continues to be an awesome career choice!” he wrote.

Heappey followed up with a second tweet: “Lots of interest in my tweet earlier about re-joining the Armed Forces. Here are the links for doing so,” before giving the sign up page for the three branches of the military.

An MOD spokesperson told Declassified: “There has recently been an increased interest in ex-military wishing to re-join the services, [so] we have taken steps to ensure that the process is as smooth as possible.”

But military personnel have made constant references to the fact the Army is still recruiting, as outlined in the Army’s internal recruitment strategy — and used the Covid-19 response to make the point.

Nick McKenzie, assistant director of Army Recruiting, tweeted on 26 April a picture of a British soldier with the words “Confidence that lasts a lifetime. Can take on even invisible enemies”, emblazoned across it. He added the hashtags #stillrecruiting and #ArmyConfidence to his tweet. He was retweeted by the Army Jobs account and Major General Neil Sexton.

Cath Possamai, chief executive of Army Recruiting Group, tweeted the day after, again using Covid-19 to push for recruits: “We are still recruiting. Our current situation has shown just how broad the @BritishArmy’s role can be, operating seamlessly in humanitarian support with the NHS and other public services.”

The image accompanying the tweet was another picture of a British soldier, with the words: “Confidence that lasts a lifetime. It’s found when the world shuts down.” Possamai added the hashtags #thisisbelonging and #inthistogether to her tweet.

We are still recruiting. Our current situation has shown just how broad the @BritishArmy’s role can be, operating seamlessly in humanitarian support with the NHS and other public services

#thisisbelonging #inthistogether pic.twitter.com/FtKpW0nb3n— Cath Possamai (@CathPossamai) April 27, 2020

Reputation laundering

The UK military became involved in the battle against Covid-19 in mid-March through two operations as part of the Military Aid to Civil Authorities (MACA) arrangement, which has previously been enacted after terrorist attacks and flooding. Operation Broadshare describes the effort to control the spread of Covid-19 in British overseas territories and military operations, while Operation Rescript oversees attempts to combat Covid-19 within the UK.

Although the government has placed 20,000 troops on “higher readiness” and reserve soldiers, sailors, and airmen have also received a Call Out Order, it is unlikely that anywhere near the 20,000 troops have been used in the response to Covid-19.

The MOD has said 150 military personnel were made available to the NHS for driving oxygen tankers, while the military’s main contribution — building the NHS Nightingale hospital at the ExCel Centre in east London — never had more than 109 soldiers on site.

The military has also delivered some personal protective equipment to hospitals and administered Covid-19 tests around the country, although it is unclear why it is performing this function.

The military sees its involvement in the Covid-19 response as a way to repair some of the damage to its reputation incurred from the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In March 2003, 83% of British people said they trusted the UK military to tell the truth about what was happening in Iraq. The level of trust has dropped to 60% today. The popular verdict on these wars was also poor, with roughly half of people surveyed saying they have made the country less safe, versus only a fraction believing the opposite.

Recasting its damaged image, the MOD wrote early on of itself as “a force for good” in the battle against Covid-19. Allusions to British military successes such as the battle against Nazi Germany have been constantly made.

In the May 2020 edition of Soldier magazine, a column by Mark Carleton-Smith, the Chief of the General Staff for the UK military, is entitled “The new frontline”. Beginning with a reference to Winston Churchill’s radio address announcing the defeat of Nazi Germany 75 years ago, Carleton-Smith writes that “our country finds itself locked in a struggle with another adversary”. He concludes: “This crisis has shown the Army at its best.”

‘It was for publicity’

The UK military has also tried to ride on the outpouring of goodwill for the NHS and other key workers.

On 29 March, Ben Wallace, the defence secretary, wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph which outlined the military’s integral role in the response. “In times like these our military contributes unique skills in medical care, but also logistics, forward planning, command and control,” he wrote. Brigadier Phil Prosser of the Royal Logistic Corps argued that “the British army soldier is a citizen soldier and is proud to be part of the response”.

On 1 April, a host of major media outlets carried stories with headlines comparing the UK military efforts to build the Nightingale hospital to the Battle of the Somme. The source was Colonel Ashleigh Boreham, who said: “My grandfather was at the Somme. This is no different. I’m just at a different battle.”

Comparing the mission to his time in Afghanistan and Iraq, Colonel Boreham said: “The difference here is that it is at scale.” He went on: “The challenges are the same, the threats are in a different way. It is more that the threat is one we can’t see.” The 54-year-old added: “It’s the biggest job I’ve ever done. But I’ve spent 27 years on a journey to this moment.”

None of the media reports noted that UK military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan contributed to serious and ongoing societal breakdown in both countries, despite the fact these operations fit much more neatly within the military’s specialisms than the current domestic crisis.

Instead, photojournalists were let in to capture the troops screwing and bolting the new facility, which aimed to house 4,000 patients. Three weeks later, it was reported that the facility had to turn patients away because of staff shortages and was being “wound down”, having been barely used.

A civilian source involved in constructing NHS Nightingale told Declassified: “I was there from day one of building the facility. The military’s presence had absolutely no bearing on the time-scale of completion.” The source added: “The military were actually not significantly involved in the construction. They were not needed. It was for publicity.” DM

Add new comment