Editorial | Of militarisation and violence: borders and bordering

David Scheuing

London: On my daily way back home I often pass by heavily armed police “safe”guarding citizens, infrastructure, life and economy: in the metro, at the station, always watchful. Yet this vigilance is neither harmless, nor innocent. It kills. This July has seen the 10th sad anniversary of Jean Charles de Menezes' killing on a stuffed metroline train in London's Stockwell Station.1

Global North:

Every day people try to cross into the minority world of the Global North. Wherever they are and attempt to cross, they are victims of surveillance, they are being analysed, digitised, and rendered “border offenders”.2 In the Arizona desert, the Mediterranean Sea, or the urban areas of Cape Town they become the “illegal immigrant” who has to be “resisted”, “deterred” and eventually troops will have to be deployed. President Obama (US) stepped up the National Guard at the southern border with Mexico, whereas the European prime ministers negotiated a military “rescue” mission in the Mediterranean Sea and thought about bombing the shores of another nationstate (Libya) to “hinder smugglers from boarding the waters”.

Both of these accounts are tied together by a simple idea: borders and their “safety and security”. The logic is that as long as the border is tight and secure, everyone and everything within is safe – therefore a loose link in the chain can endanger everything. The paradox of borders is that they are continuously crossed and thus no border can ever be “tight”.

What is a border?

What a border does is “borderwork” or “bordering” - in and at the border, but also away from its institutional set up at the border checkpoint. Police searching for “illegals” and raiding homes and businesses3, are also border agents, in that they try to divide the “citizen” from the “illegal”. Borders thus “filter” (never in a neutral way) and lend strength and credibility to nationalism, racism, and other exclusionary ideologies.

Borders are, however, a part of most people's common and daily life. Everybody faces them, but not everybody equally. They impact differently on peoples' livelihoods, prevent and enable a variety of activities (prioritised access to white bodies for example), and are always an instrument of the state.

The power of the state

States have in the last years increasingly fostered the militarisation of borders. They have rendered the border a military ground in many ways (some of them very traditional means of the military). Wars are bordered – the language of frontiers, fronts, advance and retreat work almost exclusively with the territorial marker of the borderline.

For almost 50 years after the end of the Second World War, Germany struggled to officially acknowledge the borders to the East with Poland (Oder-Neisse-Linie) as they were, too many powerful (mostly nationalist, fascist and conservative) interests questioned the validity of this war outcome. This is the very general relation of the military and the border.

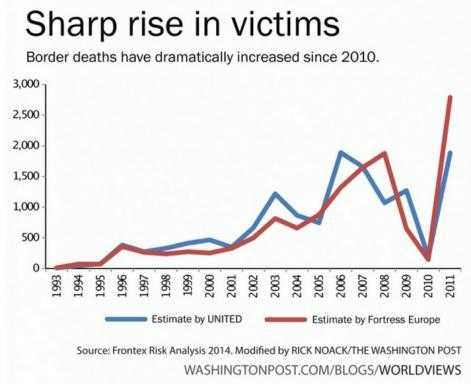

However, also at untroubled and “peaceful” borders the bureaucratic nationstate has stepped up its military intelligence (physical and knowledge), its militarised police forces, but also its language. Watchtowers, electrostatic fences, armed border guards, security checks, border deaths in the thousands4, and the language of dehumanising concern for humans at the borders: “they” are a “threat”, “they” need to be “deterred”, etc.

Challenging hegemony

But borders do not exclusively belong to state power. Too many people's lives depend on the vast borderlands of the world, too many claim stakes in borderpost services (passport facilitation, etc.), crossborder trade volumes or even petty smuggling. Too many people resist the easy divide of borders on a daily basis: by crossing rivers from India to Bangladesh and back, from Turkey into Greece and back, and so on.

What this issue of The Broken Rifle hopes to highlight is how deep and interlinked with a number of other structural levels the militarisation of borders is. We hope to illustrate vividly how this is, has been and has increasingly so in the last years become an issue of global concern. But we also want to shine a light on the numerous struggles and resistances across the globe which try to challenge this militarist status quo. What we ultimately strive for is a resounding “NO”. Noone is illegal5 and the war against people at the borders has to end – as all war is a crime against humanity.

- Nick Vaughan-Williams (2007): The Shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes: New Border Politics? In: Alternatives 32 (2007), pp. 177–195.

- Ruben Andersson (2014): Illegality Inc. Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe. University of California Press.

- See: Anti-Raid Network UK; see also: Christopher McMichael in this edition.

- Humane Borders: Arizona border deaths map project, UNITED: Fortress Europe, Border death list, watchthemed

- cf. Graswurzelrevolution no. 226, 1998

Add new comment