Against the war in Afghanistan – and/or against NATO?

Reflections on strategic issues for the antimilitarist movement

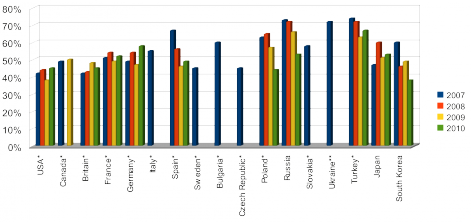

In

most NATO countries public opinion is either divided over, or in

favour of, the withdrawal of NATO troops from Afghanistan. Only in

very few countries can NATO count on support for its war (see

illustration 1). However, neither does this turn into a massive

mobilisation against the war in Afghanistan, nor does it – for now

– translate into opposition to the organisation fighting this war –

NATO (see illustration 2). So are we successful? The troops are still

in Afghanistan, so we surely must be doing something wrong.

A strategic framework

To

look at this question I am using Bill Moyer's Movement Action

Plan1 as a framework. The plan includes two important aspects: a concept of

eight stages of successful social movements, and of four roles

of activists within these movements.

A

social movement – if successful – moves from normal times

(stage 1), through proving the failure of official institutions

(stage 2) to ripening conditions (stage 3), which will lead to

the take off of the movement (stage 4). It is probably fair to

say that this is often the first time the movement is recognised as

such by the general public, or the mass media. This is followed –

often in parallel – by a perception of failure within the

movement (stage 5), and the winning of majority public opinion

(stage 6), which eventually might lead to success (stage 7),

and a continuation and extension of the struggle (stage 8). In

each stage the movement faces different challenges, and has different

strategic, medium-term objectives which it needs to reach to advance.

The

other aspect of the MAP are the four roles of activism. Any movement

needs the right balance at the right time of all four roles – the

rebel, the reformer, the citizen, and the social

change agent.

However,

it is important not to see the Movement Action Plan as a kind

of recipe for movement success. It is a useful – albeit limited –

model for understanding our movement, and for giving hints what might

now be important, but it is not a recipe for success.

For

any social movement – and for any analysis of a social movement –

it is extremely important to be clear of the objective. As Bill Moyer

points out, social movements are composed of many sub-goals and

sub-movements, which are each in their own MAP stage.

As

a WRI staff member and antimilitarist, my perspective here is the

movement against NATO, and in this I see the war in Afghanistan as a

major crime NATO is presently committing.2

However, let's have a look at both.

Where are we at: Afghanistan

As

mentioned in the introduction, the war in Afghanistan is deeply

unpopular in most NATO countries, and indeed globally. In most NATO

countries more than 45% of the population are in favour of a

withdrawal of NATO troops from Afghanistan3,

according to polls published by the Pew Global Attitudes Project,

a project shared by former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright

and former US Ambassador to the United Nations John Danforth.4

Other polls for individual countries report much higher opposition to

the war – for example, a Daily Telegraph/YouGov poll from

August 2009 showed 62% opposition to the war in Britain.5

However,

public mobilisation against the war is low – at least if we look at

major actions or demonstrations. And in the past the war in

Afghanistan has been overshadowed by the war in Iraq, to which

opposition was and is even higher.

Looking

at the movement against the war in Afghanistan, it clearly has

achieved at least phases 1–3 of the Movement Action Plan. The

conditions for a movement are ripe for a long time: the problem has

clearly been recognised, and public opinion is even more opposed to

the war than could be expected. However, it is also fair to say that

the movement has failed to use the conditions, to take it further.

This for several reasons:

The

Iraq-war might have taken up the energy of many activists, and led

to burn-out

and disempowerment.

Consequently, there is a lack of “rebels” within the

anti-Afghanistan war movement, which could launch nonviolent action

campaigns to dramatise the problem. And

without this crucial role, the movement is stuck.

A

lack of an alternative

vision for Afghanistan,

which could add credibility to the demand for withdrawal from

Afghanistan, and counter the propaganda that NATO is in Afghanistan

to fight for women's rights. Such an alternative vision can only be

developed in close co-operation with Afghan civil society and peace

movement organisations, which exist, but are not being listened to

(with few exceptions)6.A

failure to put

the issue on the public agenda:

the leaked CIA report quotes polls which indicate that few people

see the war – although they might be opposed to it – as an

important issue: “Only

a fraction (0.1-1.3 percent) of French and German respondents

identified 'Afghanistan' as the most urgent issue facing their

nation in an open-ended question, [...].

These publics ranked 'stabilizing Afghanistan' as among the lowest

priorities for US and European leaders.”7

As

Felix Kolb points out in his book “Protest

and Opportunities”,

a favourable public opinion might still be irrelevant if salience is

low8.

This

means we as a movement are failing to show how the war affects all

segments of society, but

also that we can make a difference.

I

see a need in two main areas:

local

organising

to root the movement against the war in all sectors of society, and

to bring across an alternative perspective. As Bill Moyer would put

it: the basic purpose of the movement in this stage is to

educate, convert, and involve all segments of the population. Andnonviolent

direct action campaigns,

which used intelligently can help to keep the issue on the public

agenda, reduce apathy, and counter the alternative strategies of our

governments and NATO.

However,

the public has somehow overtaken the movement, and quietly opposition

to the war in Afghanistan has risen to levels which almost indicate a

success of the movement. But as the movement did not build up its own

strength, we are not able to capitalise on it, and to really push for

withdrawal from Afghanistan. As the CIA put it in a leaked

memorandum: governments can count on apathy, and therefore ignore

public opinion. To make sure this remains so, the memorandum

suggested ways to manipulate public opinion especially in Germany and

France.9

Even

in response to a mostly apathetic public opposition, but also to the

military failure of NATO in Afghanistan, NATO and most governments

involved are changing their strategy: dates for withdrawal from

Afghanistan are set (we will see how realistic they are), and the

building up of the Afghan army and police has been stepped up

considerably. We can see a replay of the response to the opposition

to the war in Iraq: parts of Afghanistan are handed over to Afghan

security forces, which is presented to the public as a first step

towards withdrawal from Afghanistan. However, neither has a

withdrawal from Iraq really happened, nor can we take the dates being

mentioned for withdrawal from Afghanistan serious.

For

the movement to get into the next stage, there is a need to take

opportunities. A movement take-off is often a response to something

that happens – opportunities being taken. This could have been the

bombing of the tankers in Kunduz for the German movement. In other

countries there might have been other opportunities, which have not

been taken.

But

movements can also create the take-off themselves. An idea could be

to organise major events on 8 October 2011, the tenth anniversary of

the intervention in Afghanistan, which are slightly different. What

about human chains instead of the usual demonstrations? In Britain

for example from Brize Norton (the main transport hub to and from

Afghanistan via High Wycombe (RAF Strike Command) and PJHQ Northwood

to Whitehall (about 100km), thus linking important military bases and

headquarters with the seat of government. Similar human chains in

other European (and non-European) countries could create a global

human chain of 1000km – a challenge, but a challenge which could

lead to its own dynamic which could trigger the take-off of an

anti-Afghanistan war movement.

For

such an event to be successful – and more importantly, for a

movement to be successful – it is important that the different

groups and organisations within the movement work together, and

accept their differences. Even though we – as war resisters –

prefer nonviolent direct action, NVDA alone will not build a movement

or end the war. The same applies to other “roles” within the

movement: we need the reformers talking to the government, we need

the rebels (that might be us), the involvement of citizens, and the

organisers and social change agents. Only by working together and

respecting the role each one of us has to play can we be successful.

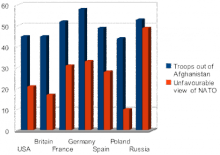

Where are we at: NATO

NATO

is a completely different matter. Public opinion against NATO

is still pretty low – 21% in the USA, 17% in Britain, around 30% in

France, Germany, and Spain, and only 10% in Poland.10

The low figure for Poland is probably representative of many of the

Eastern European new NATO countries, which see NATO much more as a

guarantor of “freedom and democracy”.11

It

is difficult to look at the movement against NATO on a European scale

– differences between the countries are very significant. The

following therefore cannot be more than a rough outline.

The

official reason for NATO's existence is to provide stability and

security for its member states. And NATO presents itself as a success

story in this regard – despite its failure in Afghanistan. As a

movement against NATO, it is therefore an important objective to show

clearly that NATO as an institution is failing to provide security,

that NATO is part of the problem, and not part of the solution.

Renate

Wanie of the German Werkstatt für

gewaltfreie Aktion Baden (Workshop for Nonviolent Action Baden)

wrote already in 2009 that “education about NATO's

war policy and the myth of the defence alliance” has to be one

of five important objectives of the peace movement after the NATO

protests in Strasbourg in April 200912.

For

us as war resisters with a focus on nonviolent direct action, there

is a specific task at the present stage of the anti-NATO movement:

“to create small, nonviolent demonstrations and campaigns that

can serve as prototype models and a training ground for the take-off

stages”.13

However, it is important that this does not happen in isolation from

the rest of the movement, but serves to strengthen it.

Last

years actions at the NATO summit in Strasbourg could have moved the

movement forward, but an opportunity was lost due to the violence

that overshadowed the entire protest.14

To prevent violence at protests – whether it is provoked by the

police or committed by parts of the movements that believe in

violence – is crucial for any social movement that wants to be

successful, as violence leads to alienation, and ultimately harms the

movement.

Nevertheless,

we are making some progress, and the powers that are can feel it. As

the Madeline Albright report “NATO 2020: Assured Security; Dynamic

Engagement” stresses, “NATO populations should be reminded

that the alliance serves their interests through the security it

provides”.15

This is a consequence of growing scepticism about the need and

usefulness of NATO – something we need to build on.

Our role in the movements

As

war resisters – as antimilitarists and pacifists – we have a

specific role to play in the movements against the war in Afghanistan

and against NATO. Although within WRI we have a variety of political

perspectives and approaches, what unites us is a principled stand

against war and militarism, and in favour of nonviolence. Both are

crucial within both movements.

As

pacifists, we will remain the minority in the anti-war movement. But

our insights into the need for nonviolence, and our experience with

nonviolent action, is highly important, as especially the events from

the NATO summit in Strasbourg in April 2009 show.

In

the coming years, we should continue to work with the national and

international coalitions against the war in Afghanistan, and against

NATO, and to push for more democratic forms of organising, and

creative nonviolent action. As Bill Moyer puts it: “participatory

democracy is a key means for resolving today's awesome societal

problems and for establishing a just and sustainable world for

everyone”.16

This requires empowered citizens, and our movements are the place

where empowerment is to take place. But this requires much more

democracy and grassroots organisation within our movements, and less

hierarchical and “professional” anti-war organising.

Questions

of war and peace are too important to leave them to NATO, or to

governments and politicians. Let's do it!

Andreas

Speck

September

2010

Notes

1Bill

Moyer et al, Doing Democracy. The MAP Model for Organizing Social

Movements, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, 2001. A

brief description of the MAP can be found at

http://wri-irg.org/wiki/index.php/The+Movement+Action+Plan

2On

the relevance of Afghanistan for NATO see the article of Tobias

Pflüger in this issue of The

Broken Rifle

5The

Daily Telegraph, Two thirds want British troops home from

Afghanistan, 29 August 2009,

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/afghanistan/6106201/Two-thirds-want-British-troops-home-from-Afghanistan.html,

accessed 9 September 2010

6Ross

Eventon, Transnational Institute: Afghan Voices and Our

Victories, September 2010, unpublished, but a good read.

8Felix

Kolb, Protest and Opportunities. The Political Outcomes of Social

Movements. Frankfurt/New York 2007

9CIA

Red Cell, Afghanistan: Sustaining West European Support for the

NATO-led Mission—Why Counting on Apathy Might Not Be Enough

(C//NF), 11 March 2010, published by Wikileaks at

http://file.wikileaks.org/file/cia-afghanistan.pdf,

accessed 9 September 2010

10Pew

Global, 27-Nation Pew Global Attitudes Survey, 17 June 2010,

http://pewglobal.org/files/pdf/Pew-Global-Attitudes-Spring-2010-Report.pdf,

accessed 9 September 2010.

11It

is important to note that another survey – Transatlantic Trends,

published by the German Marshall Fund of the United States – lists

very different figures for some of the countries, with especially

higher scepticism towards NATO in Eastern Europe. See

http://www.gmfus.org/trends/doc/2009_English_Top.pdf,

accessed 9 September 2010

12Renate

Wanie, Pacefahne oder Hasskappe - wir müssen uns entscheiden!

In: Friedensforum 3/2009,

http://www.friedenskooperative.de/ff/ff09/3-21.htm,

accessed 15 September 2010

13Bill

Moyer et al, Doing Democracy. The MAP Model for Organizing Social

Movements, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, 2001. Page

53

14Andreas

Speck: After Strasbourg: On dealing with violence in one's own

ranks, 20 April 2009, http://wri-irg.org/node/7270,

accessed 16 September 2010

15NATO:

NATO 2020: Assured Security; Dynamic Engagement. Analysis and

Recommendations of the Group of Experts on a New Strategic Concept

for NATO, 17 May 2010,

http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_63654.htm,

accessed 9 September 2010

16Bill

Moyer et al, Doing Democracy. The MAP Model for Organizing Social

Movements, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, 2001. Page

19

Add new comment