Resistance

Resources from the organisation Witness detail how to film protests and police conduct and on filming the police in the USA.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)’s ‘Mobile Justice’ app allows the user to record interactions with the police and send them to the ACLU once recording is completed. The footage is automatically sent if the phone is shaken meaning that it is not lost if the police confiscate the phone.

A similar app, ‘Nós por Nós’, exists in Brazil. Footage is saved to the cloud so that it cannot be destroyed by the police. It also provides information about rights. Users have the option to remain anonymous and the Rio de Janiero Youth Forum that designed the app then passes the material on to the appropriate public institution.

The Riot #ID project is a civic media project helping people identify, monitor and record the use of riot control against civilians through their Twitter account and printable #riotID pocket book.

Contact details for many organisations resisting police militarisation can be found on the country profile pages. If you know of an organisation or campaign that should be featured in this web resource but isn’t, please get in touch at info@wri-irg.org. This page highlights examples of resistance from around the world in the hope that movements from diverse countries can find inspiration in each other:

Kenya

Organisations such as Chemchemi Ya Ukweli (CYU) identify community-based policing as an answer to growing levels of crime and violence. This is an approach to policing that brings together the police, civil society and local communities to develop local solutions to local safety and security concerns and hold the police accountable. The Kenyan police service is currently undergoing reforms based on recommendations which suggest that community policing should be a central pillar of policing within Kenya. Recently, the police response to terrorism has changed the dynamics and put all the efforts invested in community policing at risk. The use of unnecessary force and extrajudicial killings has angered communities. The CYU advocates an approach which addresses the issues that are driving young people towards terrorist groups and criminal gangs and offers amnesty and support with reintegration for returnees in place of ever more militarised policing. Source: Oluoch, 2017.

Brazil

In Rio de Janiero, community communicators such as Gizele Martins are challenging the media narrative which treats the faveladxs (people who live in the favelas) as numbers instead of human beings. Journalists are trained to cover favela news using helmets and bullet-proof vests. The logic is that people from the favelas are dangerous and criminals. Community journalists use names and surnames and talk about the impacts of militarised policing on daily life. They talk about culture and music and strengthen the black and indigenous identity of the faveladxs. They challenge journalists, politicians and NGOs who are in favour of militarisation and who receive finance from or otherwise work with the police. This strategy is working as can be seen from the example of a politician who set up a Truth Commission to investigate human rights abuses in the favelas but did not speak to the residents. When community communicators started talking about how racist this approach is, the politician apologised and began to talk to the faveladxs.

Palestine / Israel

Gun Free Kitchen Tables is a campaign of feminist and civil society organisations in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories working on the issue of killings carried out in the home using guns taken home by security guards. They chose this as a public campaign because it is less taboo than challenging the police or the military. They carry out research and join the dots between the individual stories that are reported in the media. The media has now begun to report additional information about the owner, company and type of gun when such incidents occur and talk about it as a phenomenon rather than just isolated incidents. They are also working on two civil suits against the state and private security companies on behalf of survivors.

United States

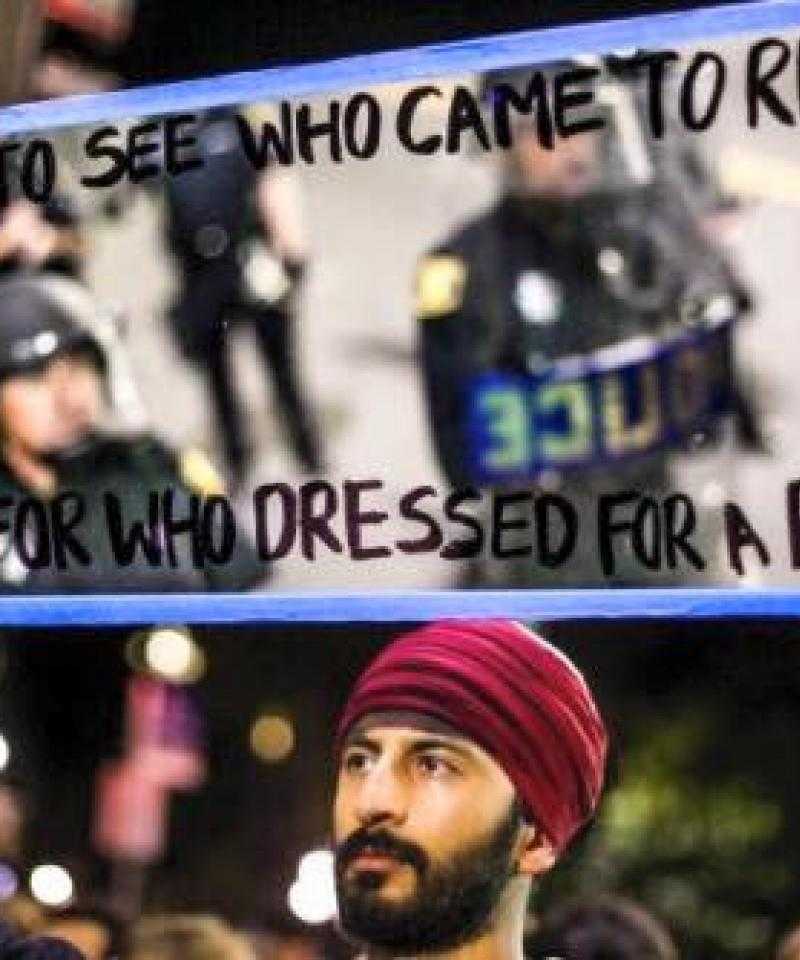

War Resisters’ League in the United States ask two essential questions: “How did we end up on this course of heightened police militarization? And, more importantly, how can we stop it?” They focus their campaigning on the Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) trainings that take place at arms fairs such as Urban Shield because trainings get to ‘the mentality of militarism’. They have carried out research into six SWAT trainings that take place across the United States, seeding cross-community campaigns to resist them. This has provided a way for groups to collaborate across a wide variety of identities and ideologies. They often fail to reach out beyond the ‘activist class’ and are currently seeking to shift their organising strategies so that they can upscale their work in a way that is needed to shift power, taking inspiration from the indigenous-led Dakota Access pipeline protests at Standing Rock and the consciousness-shifting work of the Black Lives Matter movement. Source: (Tabassi and Issa, 2017).

Africa

WoMin is a regional alliance of African women that organises in extractives-impacted communities making the links between gender, militarism and the extractive industries. They work with about fifty allied organisations in fourteen countries across southern, eastern and western Africa. This is ground-breaking work because the women’s rights organisations they work with have generally focused on more ‘traditional’ gender issues, which can present a challenge. They say that alternatives to the extractivist developmental model “need to emerge from communities, and women specifically, and their lived… practices and aspirations”. Source: (Hargreaves, 2016).

South Africa

The Casspir Project is an art installation that reclaims the legacy of the Casspir military vehicle widely used by police in apartheid-era South Africa. A decommissioned Casspir has been restored and refitted with panels of glass beadwork arrayed in traditional patterns made by artisans from Zimbabwe and the Mpumalanga province of South Africa. The artist behind the project, Ralph Ziman, recalls columns of Casspirs heading for the townships with “heavily armed paramilitary police sitting casually on the roofs brandishing automatic weapons”. The Casspir was synonymous with terror and institutional oppression. Left to rust at the end of apartheid, they have since resurfaced in multiple locations around the world including Ferguson, United States, and more recently Durban. To Ziman, the project is an “effort to reconcile a history of devastation and foster a dialogue of where we are going and what kind of world we want to live in once we get there”. Source: (The Casspir Project, 2017).

International solidarity

As this web resource attempts to demonstrate, the militarisation of policing is not a phenomenon peculiar to an individual country that occurs in isolation but a process that has much in common with and connections to similar processes happening elsewhere. Increasingly, activists working against the militarisation of policing are coming together to pool their collective strengths and work towards ending the militarisation of policing globally. Much of this activity is focused on campaigning around the export of militarised police trainings and equipment because these are clear examples of where militarised policing cultures cross-pollinate. Sometimes it takes the form of practical solidarity: in 2014 after the militarised occupation of black communities in Ferguson, United States, hundreds of Palestinians supported activists through social media by identifying tear gas canister companies and giving tips on how to alleviate the symptoms of having being tear gassed. We hope that this web resource will give you the tools to make more connections between what is happening in diverse countries around the world and spark more joint campaigns to put the militarisation of policing into reverse globally.