Equipment, training and tactics

IDENTIFICATION OF EQUIPMENT

The Omega Research Foundation (ORF) has “one of the most comprehensive archives of data on military, security and policing equipment available to researchers” including a glossary and visual glossary “designed to help human rights monitors, researchers, campaigners and journalists recognise the different types of equipment used by law enforcement officers and accurately report on the equipment”.

They recommend that their glossaries are used in conjunction with Amnesty International's publication “Monitoring and Investigating Equipment Used in Human Rights Abuses” and www.mispo.org, which is a platform which gathers “images of military, security and police equipment from across the globe, using a network of international photojournalists, photo agencies and NGO field workers”.

The ORF is part of the Riot #ID project, a civic media project helping people identify, monitor and record the use of riot control against civilians through their Twitter account and printable #riotID pocket book.

ARMS FAIRS SELLING POLICE AND SECURITY EQUIPMENT

The ORF also produces a map of arms fairs held all over the world including many which exhibit security and policing equipment or host trainings.

The militarised mindset is nurtured by police trainings which simulate scenarios of extreme threat and encourage knee-jerk militarised responses, setting non-police actors up as the enemy. In the United States, the National Tactical Officers Association (NTOA) runs a training called ‘Talk-Fight-Shoot-Leave’ which “encourages use-of-force solutions and ‘warrior mentalities’ over de-escalation tactics” (Tabassi and Issa, 2016). Such trainings are also often racist, such as the Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) trainings held in the United States which use negative racial stereotypes in their dramatisations and regularly host Islamophobic speakers. Participation in militarised training normalises extreme policing responses to exceptional circumstances and the attitudes that are promoted in them are increasingly seeping into everyday policing. In the United States, there appears to be a direct correlation between the proliferation of SWAT trainings and the rise in the number of SWAT raids which are most commonly carried out in response to commonplace policing situations (Tabassi and Issa, 2016).

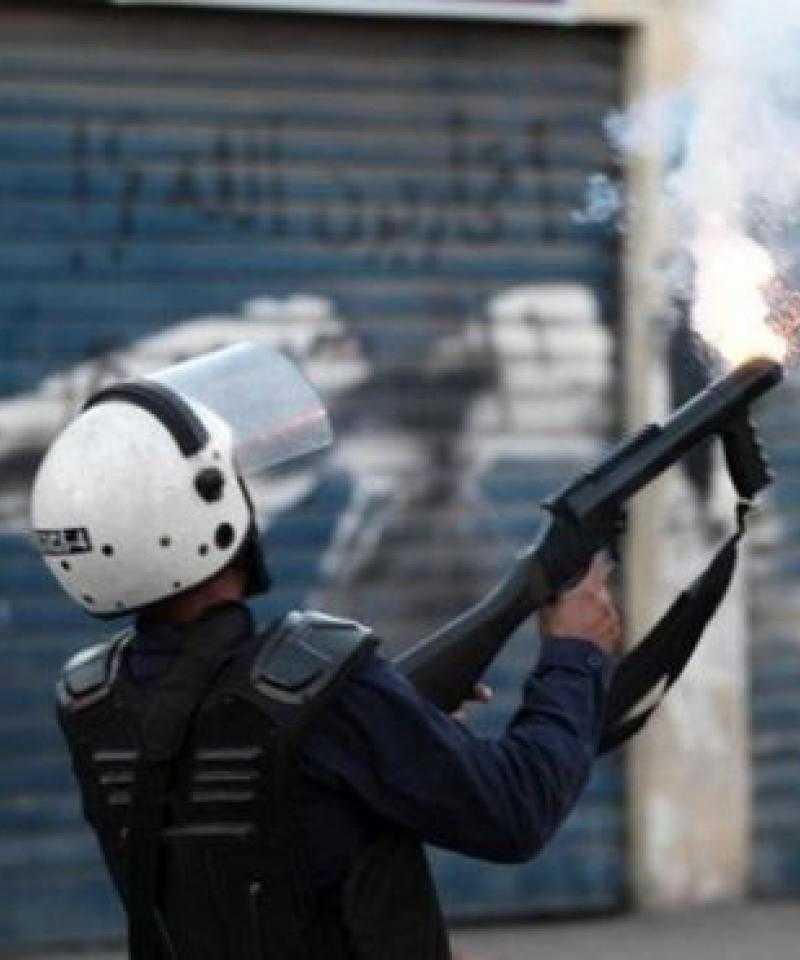

There is a widespread use of militaristic tactics and weaponry. Sometimes actual military weapons find their way from the military into the hands of the police. In the United States, the Pentagon’s 1033 Program has transferred more than $US 5 billion of military equipment to police departments since 1990 and in Mexico, 156,419 arms were sold by the military to state police agencies between 2010 and 2015. ‘Non-lethal’ weapons such as tear gas (prohibited for military use) and rubber bullets are effective at multiplying force and controlling crowds and are reminiscent of the weapons of the battlefield. Whilst theoretically non-lethal, they frequently injure and can even kill. The helmets and shields worn by riot police the world over act as a mask and put up a barrier between police and protester and new technology such as remote-controlled vehicles that can disperse tear gas over demonstrators holds the potential to further distance the police from those being policed, accentuating the ‘us and them’ mentality. Policing tactics are often indiscriminate and disproportionate to the threat posed and can be indistinguishable from those of the army uses against enemy combatants, with Israeli snipers shooting-to-kill Palestinian demonstrators and U.S. SWAT teams, “dressed in military gear and weapons” assaulting and forcefully entering up to 137 homes a day, “often throwing grenades first” (Tabassi and Dey, 2016).

Trainings are one of the key mechanisms through which militarised policing is exported and militarised mentalities and ideologies shared. In the run-up to Brazil hosting the World Cup in 2014 and Olympics in 2016, the Brazilian police received training from both the Israeli company International Security & Defence Systems (ISDS) – primarily from ex-military personnel – and the infamous U.S. private military and security company Blackwater, with military and federal police officers travelling to North Carolina for a three-week training course focusing on civil disturbances and fighting terrorism paid for by the U.S. government. Protests against the social cleansing of the neighbourhoods surrounding the sporting venues were met by the Brazilian police with pepper spray and rubber bullets. The police trainings and military cooperation are implicated in the consolidation of “an authoritarian, punitive – and failed – public security model” and contributing to bringing “existing state violence to an even more dramatic level” (Maren and Sanchez, 2015). Israeli military and security companies train police forces from around the world in the techniques and methods learnt from the occupation and their tactics are adopted by their trainees. Watchtowers similar to those in use on Israel’s apartheid wall are being constructed in the favelas of Rio de Janiero to watch and control the population and are also used by snipers. International police trainings also take place at arms fairs such as Urban Shield in California which are attended by police forces from countries such as Bahrain, Norway and Singapore or are hosted by organisations such as the International Association of the Chiefs of Police (ICAP).

The sale of equipment is another way in which militarised policing is exported and this also takes place at arms fairs including fairs specialising in the sale of policing and security equipment such as Security and Policing in the United Kingdom and Milipol in France. Jamal Juma’, coordinator of Stop the Wall, describes how Israel tests a variety of techniques and weaponry such as tear gas and dum-dum bullets against Palestinian protesters which are then promoted abroad to other oppressive regimes.