Julián's Story

Return to Conscientious Objection: A Practical Companion for Movements

Julián Andrés Ovalle was born in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1981. For ten years, he was part of Acción Colectiva de Objetores y Objetoras de Conciencia (ACOOC, Conscientious Objectors' Collective Action), an organisation which aims to create the concrete conditions for people to be able to opt for alternatives to militarism, specifically alternatives to obligatory military service in Colombia. Currently, he is working towards the consolidation of a Latin American and Caribbean Antimilitarist Network. Here, he writes about being a conscientious objector on the grounds of his pacifism in Colombia.

The persistence of wars is shocking evidence that people are the ones who sustain them. It’s not just the major powers, those with industrial interests or armies; we individuals from all over the world provide financing and legitimacy which keeps weapons firing indiscriminately. It is not just neoliberal interest in controlling land for the exploitation of its natural resources, it is also our everyday consumption which enables large companies to continue extracting, producing, and selling for profit.

When we speak of war it evokes the image of a soldier – a warrior, armed from head to foot, advancing through hostile territories. But little attention is paid to the patriarchal aspect of the military, to the uniformed man, at once one who submits and one who attacks, one who rejects any questioning of his masculinity. That odious figure pressing men — and women — towards a state of social normality where sexually different bodies seem to be a mismatched rarity, where the only way of being a man is to be a warrior always at the ready. Talk of war focuses awareness on the need to maintain the unity of states and national borders, making legal use of force in accordance with personal, institutional or even business interests. When you leave aside the subject of war, then we can talk about gender diversity and nationality. We can even speak about the power of diversity in the international meeting of individuals and peoples, an encounter which gives rise to interracial dating and working together, as has been possible in Latin America, where I was born.

The history of Latin American countries makes many people approve of armed struggle as a means to achieve independence and human dignity. However, there are millions of us who, having evaluated it as a strategy for social change, do not believe in violence. And it is not only ideological rejection: it is a rejection of violence borne from analysis and historical reflection, from the results of armed confrontations between the states and insurgent groups that they have unleashed – and still unleash – in our countries.

Dictatorships have shown that lack of legitimacy requires force to be used. Armed insurgent struggles in Central and South America have demonstrated and continue to demonstrate the cost of rebuilding a broken social fabric. Colombia, the country where I was born, has been at war for over sixty years. A war which has caused millions of deaths and internally displaced persons and which, after several failed peace processes, is now in a new phase which would appear to be the final one. Or at least this is what the majority of the population hopes.

Before the groups in confrontation decided to negotiate, thousands of innocent people were shot. For example, my father, who after a military attack – which, it goes without saying, was illegal – is still alive and kicking; and we go on living because we stopped the cycle of violence that they wanted us to engage in, the one that never ends

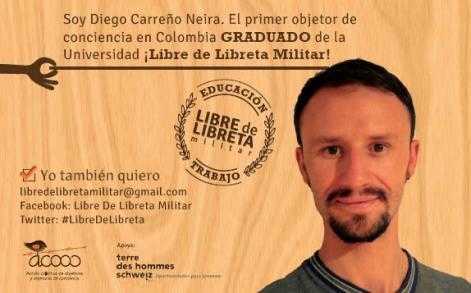

I feel motivated to continue to resist violence because we are still alive and I know that changes are only achieved through perseverance and persistence. So, in addition to not enlisting myself in the Colombian army and doing compulsory military service, I decided not to pay for the issue of the 'Military Booklet', a document which would certify me as a reservist (even without any training) and which would allow me to graduate as a psychologist from university. Because of this, it was only after a long struggle to make visible this and other restrictions to civilian life which are imposed on those of us who are decidedly outside the entire violent military system that, ten years after starting my studies, on 25 March 2015 I was able to receive my professional title.

I think listening to the despair of people around me who have grown up with and are victims of the war, and at the same time being aware of the achievements of the conscientious objectors in Colombia, reaffirms to me that whilst we still cannot perceive a less militaristic world, I will continue building new and creative ways for the countless millions of people dissatisfied with the violence. We will continue gaining space to live a happy life and have a death that is the result of living life and not from someone else's decision.

Translated from Spanish by Ruby Stearhart

Add new comment