21st Century War Profiteering: more openings to object?

Return to Conscientious Objection: A Practical Companion for Movements

Hannah Brock gives us an historical example of objection to war profiteering which conscientious objection movements today could emulate.1

The introduction to this book puts the following question: 'and what of the future? Conscientious objection movements have often been inspired by the old expression 'imagine if there was a war and no one showed up?'. Well, soon perhaps hardly anyone will need to show up for there to be a war, as technology 'advances' and can do the killing of 1,000 armed people at the touch of a button. Increasingly, professional armies using remote control weapons, private security firms and robots have taken over from the mass armies of the mid 21st century. Yet even with these 'advances', you still need people to wage war. Those people are increasingly not members of the armed forces however, but instead the 'civilian' branches of the supply chains for weapons and the militarism that make war inevitable. This opens up whole new vistas of people who might resist war and their part in it.

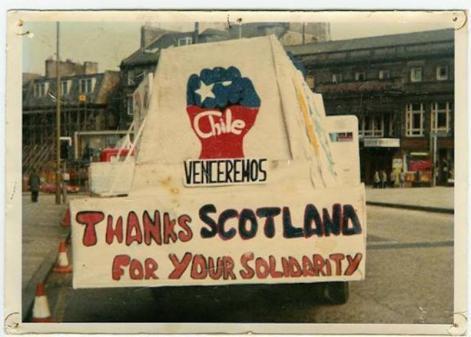

One key aspect of this is the economic trade behind (and after) wars. War Resisters' International (WRI) calls this 'war profiteering', which we define as every economic activity that either profits from, or incentivises, war (often both). There are some inspiring past examples to give us some ideas of how forms of objection have taken place in the supply chains of war profiteers. In 1974, Bob Foulton – a worker in the Rolls Royce factory in the Scottish town of East Kilbride – was due to repair some warplane engines. However, Bob recognised them as parts of the Hawker Hunters that had attacked Chile's presidential palace during the coup of September 11, 1973. He refused to work on them, and by the end of the day, all 4,000 factory workers had joined him and refused to service the engines or to let them leave the factory. They were left outside, exposed to the elements, and were still there four years later.2

There are almost endless places where this version of conscientious objection beyond the military could be manifest: PR companies employed by arms dealers; the teachers expected to host the military in their schools; the phone companies providing coverage to occupied territories; the film makers expected to promote militarism in their blockbusters; engineers, caterers and administrators for arms dealers; workers in ports who deal with arms shipments;3 security companies expected to run prisons; car companies who start making tanks; bankers holding the money of military dictators, etc, etc, etc.

For movements of resistance to begin, however, the workers and civilians involved in these pursuits have to first recognise their role, or the role of their employer, as part of the war machine. The compartmentalised nature of contemporary trade and production is a challenge to this. To take the example of arms manufacturers, it is increasingly difficult to point at who actually builds a weapon – and therefore to evoke any feeling of responsibility. Different companies and factories and individual workers will produce a component, which might be used in another factory or country by a weapons company, but equally by a civilian company. Rather like the military personnel who control drones, there is a growing distance – an alienation – between those doing the work of war, and war's victims. Compartmentalisation allows people to believe that they're not part of the problem. As a gunsmith commented after a school massacre in the US, 'nobody wants to think they had a hand in making the Newtown gun'.4 Consciousness raising is hard work, and often more possible when a situation already has a high profile in civil society or the press – but it also takes the communications and research skills to be able to discover the supply chain and inform the workers.

Excitingly however, this kind of conscientious objection also encourages solidarity between workers and individuals – as opposed to people who see themselves as soldiers – as it did between Scotland and Chile. This field of activism is an interesting avenue to explore, especially perhaps for conscientious objection movements who have previously worked with members of the armed forces. If conscientious objection is about knocking out the labour pillar of war that make war possible, then civilian conscientious objectors will now be crucial, too.5

1. For more on Hannah's background, see Chapter 1: Conscientious Objection in History'.

2. Gardiner, Karen 2015, 'Nae Pasaran' Shares the Story of Scottish Laborers Standing Against Chile's Pinochet Regime', Vice [online] 21 April, <http://www.vice.com/read/nae-pasaran-shares-an-untold-story-of-chilean-solidarity-41>, accessed 12th June 2015.

3. Although the union itself didn't make a supportive statement, many members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union respected the 'Block the Boat' picket in Oakland, USA, in August 2014 and refused to unload a cargo from Israel's largest shipping company, ZIM. The action was protesting the Israeli bombardment of Gaza, and a response to a direct appeal by Palestinian trade union groups.

4. Twenty children and six adults were killed in Newtown, Connecticut. (Helmore, Edward 2012, 'Gunmakers' town in crisis after shootings', The Guardian [online] 22 December <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/dec/22/gunmakers-town-crisis-shootings>, accessed 12th June 2015).

5. One example we found is the group IntelExit, whose website https://www.intelexit.org/ contains an automatic resignation letter generator for those working for intelligence agencies. An example includes: 'The intelligence agency I work for has...lost its moral compass, violates fundamental freedom or democratic principles or abuses the idea of “national security“ in order to justify violations of the constitution.' They also encourage people to leave these agencies and gives reasons for doing so, online and with large bill boards and flyering outside the offices of intelligence services.

Add new comment