Repression within nonviolent activist groups

Usually when we think of repression and activism we focus on that enacted by the state through bodies such as the police. This article explores repression within activist groups. By this I mean the inhibition of the views and contributions of certain members of a group by other group members.

In a piece in the previous issue of The Broken Rifle the South Korean LGBT Human Rights activist Tomato described the hostility she felt from many villagers in Gangjeong, on Jeju island, for being a lesbian. She was one of many activists from all over South Korea who have gone to Jeju to support locals in their resistance to the construction of a new naval military base.i However, she experienced repression within a movement – a movement encompassing people with more diverse views than you would probably find in a smaller activist group, who did not share the same values and approaches, despite their common goal. I examine repression by fellow group members - internal repression on a micro level.

Using points from the critique of nonviolent resistance by Peter Gelderloos (a response to his assertion that an adherence to nonviolence is itself repressive to minority groups would require an extended or separate article), I focus on the problem of patriarchy, although I also address the process-based power inequalities present in consensus decision-making, which Howard Ryan discusses.ii I do not have space to explore other manifestations of intra-group repression, such as that of ethnic minorities. Gelderloos notes that during a U.S. antimilitarist group’s discussion on oppression in 2003 only the non-white, non-middle class members raised the issues of internal repression. It is important to recognise that our awareness of individual privilege and unequal power dynamics allows us to challenge repression within our activist groups, thus strengthening our affinity and our work.

Patriarchy

As Gelderloos states, 'Patriarchy is a form of social organisation...[which defines] clear roles (economic, social, emotional, political) for men and women, and...asserts (falsely) that these roles are natural...True to its name, it puts men in a dominant position’. Patriarchy ‘is not upheld by a powerful elite...but by everyone’; its ‘distribution of power’ is very diffuse. Most commonly it is visible in sexism (gender-based discrimination).

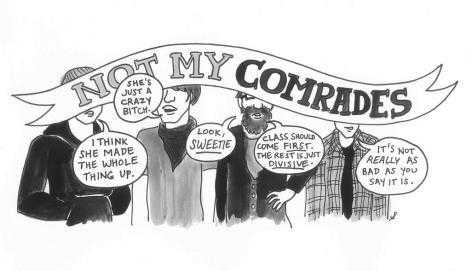

In the UK in July 2012, the city of Liverpool hosted a small ‘Sexism in Activism’ meeting, organised by Angry Women of Liverpool (coincidentally I am writing this on a coach to the same city). Attendee Adam Ford reflected that the event was particularly timely as it followed ‘a number of misogynistic incidents in and around the Liverpool activist “scene”’.iii He observes the sad paradox that ‘sexism is endemic in groups avowedly committed to equality for all.’ Those present at the Liverpool meeting considered the gender ratio within their own groups, almost all of which were found to comprise a male majority. The suggested reasons for this included ‘practical considerations such as childcare arrangements’ (two women said that children not welcome at activist meetings), but there was a strong feeling that a culture of sexual discrimination existed, which was 'severely' discouraging women’s participation. They discussed ways to counter this, citing the importance of providing safe, child-friendly spaces, but Ford admits that ‘As the meeting ended, the atmosphere was heavy...what about all the people who weren’t there?’. The more subtle comment, and the one most relevant to my article, is that on the far right: 'It's not really as bad as you say it is.'

Advice to male activists (but also relevant to females) on tackling sexism from Sisters of Resistance includes: taking on jobs ‘typically still carried out by women’ such as cleaning, looking after children and administration; ensuring that ‘the male to female ratio of speakers, facilitators, participants or chairs is always 50/50’; and (perhaps most importantly) incorporating ‘an awareness of gender and feminism into your everyday life; for if you want to bring about revolutionary change, you must begin with yourself.'iv This last point is in keeping with the need to 'call each other out', in a non-accusatory way, on our sexism, which was stressed during a discussion I attended at Warwick University’s Women's Week earlier this year. The nonviolent activism trainer George Lakey recently observed that people don't like being “called out”, partly because they don't find it helpful, but perhaps more importantly as he considers this a classist practice.v However, I have found that moments of discomfort are often when we learn the most, and as long as we do so sensitively - perhaps in private – and making it clear that we ourselves (like everyone) need to be picked up on our own repression, and that it's nothing personal. This ties in with Lakey's request that we re-frame 'anti-oppression' groups or sessions as (the far more positive) 'liberation' workshops.

Consensus decision-making

Consensus decision-making is frequently used by activist groups, but Ryan highlights three main problems with it. Firstly, ‘Every member of the group has the power to block a decision.’ This disproportionate capacity to influence the outcome often leads to unsatisfactory compromises, as the alternative would be complete ‘immobilisation’. Indeed, the threat of a block alone can have this effect. Secondly, consensus favours the voice of more confident, experienced activists. I have seen this myself, where better-informed and more assertive people dominate the discussion, and thus have a unrepresentative influence on the final decision. Thirdly, consensus can be a very protracted process, and long meetings are often not feasible for those who work long hours and who have children to look after, this privileging those who work less and who don't have dependents.

Ryan advocates the incorporation of voting, because as ‘it does not require complete unity, [it] makes it easier for people to disagree[.]’, yet it also allows more timid members to assert their individual preference through a simple raising of the hand, and it tends to be less time-consuming and less tiring. Nonetheless, as he acknowledges, voting is itself coercive because ‘the will of the majority holds sway’. He fails to mention that unless a secret ballot is used voters may feel peer-pressured into voting differently from the way that they actually consider to be best. There are several ways we can maintain the use of consensus whilst addressing some of its problems. One is to learn best practice to avoid unnecessarily-long sessions where the discussion goes around in circles. Training for this is available, both through practical sessions and courses, and online. We should ensure that those best-informed on the issue or issues related to the decision share as much of that knowledge with the others as possible before the discussion itself begins. Another positive response is to provide a child-friendly space, so that parents are incentivised to participate fully.

Conclusion

Tomato pointed out that the Gangjeong villagers ‘are not so different from me: a minority.’ Activists generally are a minority. It is imperative that we address repression within our own groups, and to do this we need to start by concertedly looking to identify it in its different forms. Then, employing positive actions – as advocated by Lakey - we can move towards liberation.

By Owen Everett, Quaker Peace & Social Witness Peaceworker at War Resisters International and Forces Watch.

Add new comment