Colombia – the reality of conscientious objection during armed conflict

Report on a visit to Colombia in May/June 2010

Andreas Speck, War Resisters' International's Right to Refuse to Kill programme worker1, visited Colombia from 19 May until 12 June 2010. During his visit, he spoke at two conferences on conscientious objection, and visited groups and individuals working on CO in Bogota, Sincelejo, Medellin, Cali, Villa Rica, and Barrancabermeja. This report gives an overview of the situation of conscientious objectors and their work in relation to the armed conflict in Colombia.

Introduction

War Resisters' International's work on conscientious objection in Colombia has a history of many years – WRI was involved in the solidarity for Luis Gabriel Caldas León2 back in 1995. However, a closer relationship with the conscientious objection movement has developed since 2006, and a joint strategy for the accompaniment of conscientious objectors has been developed, which was launched on 15 May 20073. Besides accompaniment in individual cases – especially in cases of recruitment of conscientious objectors – War Resisters' International has also engaged in the lobbying of international institutions, and of the Colombian government.

Since 1995 – and even since 2006 – the legal framework for conscientious objection in Colombia has changed to the better. And it can probably be said that the work of WRI contributed to this. The most important change is that in October 2009, the Constitutional Court of Colombia ruled that there is a right to conscientious objection to military service under the Colombian constitution – a significant change of its past jurisprudence4. The court urged the Colombian Congress to pass a law to regulate the right to conscientious objection. However, here the difficulties begin, but more on this later.

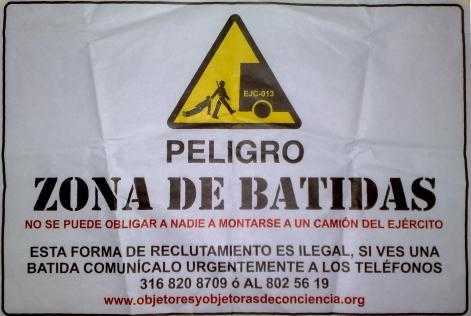

A second important improvement is some clarification on the legality of the widespread recruitment practice of 'batidas' – raids on young people in the street, during which any male youth who cannot prove that he has sorted out his military service will be forcefully recruited. In 2008, the United Nations' Working Group on Arbitrary Detention stated clearly that “the practice of batidas or recruitment round-ups, whereby young men who cannot provide proof of their military status are apprehended on the streets or in public places, has no juridical foundation or legal basis”5. In addition, the Human Rights Committee demanded in its Concluding Observations from July 2010 from Colombia to revise the practice of 'batidas'6.

The Colombian military was forced to repeatedly state that it does not do 'batidas'7. However, the practice is very different8, and if there have been changes, there certainly have not been improvements.

The situation of conscientious objectors today

In a country like Colombia, with strong regional differences, also the situation of conscientious objectors differs from region to region – not legally, but in practice. The first major difference is between city and country – and within the cities between the more affluent parts and the “popular” (meaning: poor) neighbourhoods. But there are also considerable differences between different parts of the countryside.

Bogotá

I arrived in Bogotá on 19 May, coming from Buenos Aires, where I had a brief stopover after more than a week in Asunción in Paraguay. I had been invited by Acción Colectiva de Objetores y Objetores de Conciencia (ACOOC)9 to participate in an international conference, which took place on 2 June.

In this conference, ACOOC cooperated with the Swedish NGO Civis, the Grupo de Derecho de Interés Público Universidad de los Andes, and CINEP - Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular.

One of the objectives of the conference was to analyse the legal and practical situation following the sentence of the Constitutional Court of Colombia. However, on of the difficulties was (and still is at the time of writing) that the sentence itself has not yet been published. Although the sentence is from 14 October 2009, until now – nine months later – only the press communiqué of the court is available10.

The conference included a range of international and national speakers. In my own presentation, I focused on the possible strategies and challenges for the conscientious objection movement after the sentence of the Constitutional Court, and pointed to the need to promote conscientious objection as an antimilitarist perspective. I also cautioned against lobbying for legislation, as in the present political climate an legislation is likely to be pretty bad, falling short of an implementation of international standards on conscientious objection11.

Another aspect is the practice of recruitment. ACOOC has been monitoring not only 'batidas', but also irregularities during the normal “jornadas de reclutamiento”, massive recruitment drives about four times a year. Although this is the legal form of recruitment, often youth reporting to the recruitment station are not informed of their rights, health problems or reasons for exemption or postponement are ignored. ACOOC therefore works on information on the illegality of batidas, and the rights of young people during military recruitment.

One evening I went to Soacha, a small town on the outskirts of Bogota, to a presentation of a report Soacha: Lu punta del iceberg. Falsos positivos e impunidad12 (Soacha: the tip of the iceberg. False positives and impunity) by Fundacion para la Educacion y el Desarollo (FEDES). The report documents the case of 16 so-called “false positives”, normal youth or even conscripts killed by the military and the presented as members of the guerilla. These 16 are only the tip of the iceberg – estimates of false positives are as high as 3,000.

Many youth in Soacha are thinking of declaring themselves conscientious objectors, also as a consequence of the experience of violence13.

Sincelejo / Sucre

From Bogota I travelled to meet the activists from PazCaribe Sincelejo14 and Red Juvenil Sincelejo in Tolu, a small Colombian tourist town on the Caribbean coast, close to Montes de Maria. The situation in Sincelejo and in the department of Sucre is very different from the one in Bogota. PazCaribe Sincelejo works in Montes de Maria, a small region in the north of the departments Sucre and Bolivar, which has been chosen as the Peace Laboratorio III of the European Commission15.

The region, 15 municipalities in the departments of Sucre and Bolivar, has some of the best land in the country. The zone is strategic, as it is rugged terrain, with lots of hiding places, sitting right between nearby coca-producing zones and the Caribbean Sea. While the Montes de Maria is not a coca-growing area, the Gulf of Morrosquillo, a bay scooped out of the coast south of San Onofre, has long been a jumping-off point for boats carrying tons of cocaine every year.

Because of the fertile land, there is a growing interest to grow palm trees (palma africana) for palm oil production, and sugar cane (for the production of ethanol) – both with environmental and social consequences. To serve the interests of agribusiness, local farmers need to be displaced, to clear the land for palm trees and sugar cane.

As a consequence, in the past decade, the region experienced a lot of violence and displacement, mostly due to actions by the guerilla, paramilitaries, and the Colombian military, and only in recent years some of those displaced returned. In May 2010, the leader of the regional Association of the Victims, Rogelio Martínez, was murdered by paramilitaries16.

This is the context of conscientious objection in Sucre and especially in Montes de Maria. PazCaribe, and especially Red Juvenil PazCaribe, work with young people in Montes de Maria mostly on empowerment and prevention of recruitment (“Si Quieres la Paz? No te Prepares para la Guerra!!!” – If you really want peace? Don't prepare yourself for war!!!). The work is using art and music as ways to express the needs and ideas of youth.

Red Juvenil PazCaribe is an active movement which works with young people, organisations, churches, individuals and groups that believe in the construction of a better Caribbean, and conscientiously objecting to all manifestations and acts that promote violence. Besides conscientious objection, Red Juvenil PazCaribe organises workshops on active nonviolence17.

Presently, War Resisters' International and PazCaribe are discussing how to organise the visit of medium term volunteers to Sincelejo, and possibly other forms of solidarity visits. In addition, there is the idea of a speaking tour of conscientious objectors from Sucre and Bolivar in Europe or the USA.

Barrancabermeja

Barrancabermeja is an industrial town on the river Magdalena, in the region Magdalenia Medio in the department of Santander. Barrancabermeja is home for the biggest petroleum refinery in Colombia, which is owned by the state company Ecopetrol. Petroleum and farming comprise most of city's economic activity.

Barrancabermeja has seen extensive fighting between the various armed groups in Colombia's ongoing civil war. On May 16, 1998, a large group of paramilitaries swept through the city, killing 11 people and kidnapping 25, who were later killed. This massacre signalled the beginning of the takeover of the city by the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), which would culminate in 2001. During the final year of the invasion, 539 people were killed. Although the AUC were officially demobilised in 2006, follow-up groups such as the Aguilas Negras are still active in the city, and death threats against human rights activists are frequent.

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the country's largest guerilla group, remains active in the surrounding countryside.

The local CO group Quinto Mandamiento18 grew out of Organización Feminina Popular19, one of the countries largest women's peace movements. The work of Quinto Mandamiento in the last few years has been impressive. I first visited Barrancabermeja in May 2007, during the time conscientious objector Carlos Andres Giraldo Hincapie20, who had been recruited in a batida, was forced to serve his military service in Barrancabermeja. Back then we had a meeting with the local military commanders, who insisted that the recruitment of Carlos Andres Giraldo Hincapie had been legal. While the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention proved them wrong21, this came too late for Carlos Andres Giraldo Hincapie.

On 3 June, we again had a meeting which also involved the military, but in which also participated representatives from other NGOs and from the mayor's office, which since the election of Carlos Alberto Contreras in 2007 is more progressive. During the meeting it became clear that the military is under pressure to recruit, and can't recruit sufficient numbers without batidas, simply because many young people do not show up. Consequently, the local military commanders denied that batidas are illegal, although the national recruitment department and the Ministry of Defence are clear about this.

While there seems to be some agreement at present that known members of Quinto Mandamiento are not recruited, this is still a bit problematic. On the one hand it is questionable whether it is wise to pass on the names and probably ID numbers of conscientious objectors to the military. On the other hand, someone who is not on the list of Quinto Mandamiento can still be a conscientious objector. And when I insisted that even a serving conscripts can develop a conscientious objection, and has the right to CO, you could see in the faces of the militaries that they didn't like it.

In Barrancabermeja too a conference on conscientious objection was organised, with a slightly different programme, and a different audience. About 200 people participated – mostly young people – and the presentations focused more on the right to conscientious objection, and the right of young people in situations of recruitment.

On the next morning we had a meeting with participants from a local youth group from area, Quinto Mandamiento, Red Juvenil de Medellin, ACOOC, Civis, and WRI. The reports we heard especially from rural areas made it very clear how military recruitment is an attack on the freedom of young people. We heard that the military is basically present wherever young people might want to go – football matches, concerts, fiestas, etc. The presence of military checking the military status of young people at events such as these makes it a risky activity for any young man to go out, and enjoy himself – he could find himself in the military much faster than he would like.

Cali

After my brief stay in Barrancabermeja, I travelled to Cali, to visit the small group of conscientious objectors – the Colectivo Objetarte22 – there. The group in Cali has always been small, but at present it is especially weak, and so the focus is more on cultural activities to promote nonviolence and conscientious objection. While I was there, the next upcoming activity was a concert on 20 July.

Villa Rica

Villa Rica is a small town of Afro-Colombians in Norte del Cauca, about 30 minutes from Cali. There, two organisations work on conscientious objection – the Corporacion Colombia Joven, and Fundacion Villa Rica, better known under the name of its cultural project, the Hip Hop group Soporte Klan.

An important part of the work of both organisations is the rediscovery of the cultural heritage of Afro-Colombians, who were brought to Colombia as slaves to work on the sugar cane plantations. Slavery was only abolished in 1851, and Villa Rica was one of the last towns in which the slaves gained their freedom.

Until today, Villa Rica is surrounded by sugar cane, and only few families still own their land, and grow their own food on their 'finca'. Decades ago, most have been forced to sell to the sugar cane barons.

In the past, the land grab of the sugar barons worked in a clever but dirty way: when families refused to sell their land, it would be fumigated from the air, to destroy the crops. Without a harvest, the families were then easy victims for the agents of the sugar barons, who offered them money in exchange for renting the land for one crop cycle. They then planted sugar cane and used a lot of pesticides, so that when the land was returned to the families, they could no longer grow their crop. So the sugar barons again sent their agents offering to buy the land – but for cheap. Many families felt they had no other option, and so sold. Pressure and threads by paramilitaries were used to increase the pressure.

Today, there again is pressure on the remaining families to also sell. Soporte Klan has launched the campaign Haga que pase (Make it happen) to support those families, and to reclaim back some of the land that has been lost.

And the land grab is at the core of the armed conflict in Colombia, conscientious objection is part of that work, and more so prevention of recruitment. Due to the economical situation of many people in Villa Rica, military service, although badly paid, is often seen as a way out of poverty – at least one person less to feed and house during the time of service.

Medellin

Medellin, the second largest city of Colombia, is one of the centres of the Colombian conscientious objection movement. Red Juvenil de Medellin23 is a quite strong youth network, and its work includes the promotion of conscientious objection, alongside popular education, active nonviolence, and the use of art and music.

In the poor neighbourhoods of Medellin, and at public transport hubs, 'batidas' are widespread. But besides recruitment by the official state military, there is also recruitment by paramilitaries, drug gangs, and the guerilla. Violence and crime are widespread – and mostly the violence and crime is poor on poor. The upper classes live in neighbourhoods with private security, fenced in with electrical fences.

Red Juvenil has been working a lot on informing young people about their rights in situations of recruitment, and especially about the illegality of batidas, and the right to conscientious objection. As part of this work, they go to the recruitment stations during recruitment rallies and hand out information and speak to young people queuing there to get recruited, and who might not be aware of their rights.

And they also provide legal, political, and moral support to conscientious objectors, or young people who got recruited against their will.

At Red Juvenil the work on conscientious objection is part of their antimilitarist perspective, based on nonviolence as a way of life.

What now after the judgement of the Constitutional Court?

While the judgement of the Constitutional Court is a huge victory, it also poses new challenges for the CO movement. One of the problems at present is that the wording of the judgement is not yet known – more than nice months later. This means it is not known what restrictions the Court might be placing on the right to conscientious objection.

For the time before the Colombian Congress passes a law, the Court pointed to the legal tool of the tutela (writ for protection) in cases where the military does not recognise the right to CO. How this will work in practice, and how this can work especially in the context of batidas, remains to be seen. Will a CO recruited during a batida be released while the tutela is pending? Or what will happen?

The second problem is more difficult to solve, as it is related to the different political perspectives of the CO groups and their supporters – NGOs and universities – about the strategy in relation to a CO law. While all groups agree that the judgement of the Constitutional Court means progress in terms of the protection of COs, they disagree about their strategy in the present situation. Should they and if so how engage with the process of drafting a law on conscientious objection? What 'restrictions' would they be willing to accept? What about substitute service.

Groups coming more from a tradition of nonviolent resistance such as Red Juvenil are opposed to a law on conscientious objection, which would regulate and restrict the right to conscientious objection. Others are concerned about what a law might say in the end, but are not as clearly opposed to a law. And others are clearly in favour of a law on conscientious objection, and see it as an important first step.

Conscientious objection – more than refusing military service

For most of the groups in Colombia, conscientious objection is about much more than refusing military service. While there are important differences among the groups about strategy and tactic around conscientious objection – not only about substitute service, but more generally about the role of a law recognising conscientious objection, and about the way to get to such a law – they are united in their opposition to all armed actors in the armed conflict, be they linked to the state (military and paramilitaries), or to any of the guerilla factions (FARC and ELN are the two most important ones, but not the only ones).

Nonviolence as a way of life, but also as a strategy of resistance, is an important basis for the work of the groups, and out of this nonviolence also a critique of the structural violence in Colombia (and globally). And this structural violence continues to fuel the armed conflict in the country – many of the poor don't see any other option than to join one of the armed groups to make a living, and the rich need to military and paramilitaries to protect their interests.

Conscientious objection is a way to resist this cycle of violence and militarisation, which keeps the country stuck in armed conflict. Many people are tired of it, but do not see a way out. Or they voted for Santos, who is promoting a military solution to it – which hasn't been possible in the last 50 years.

Conscientious objectors promote another way out. Taking responsibility, resisting militarism, and promoting nonviolence.

Andreas Speck, August 2010

Notes

1 More information on War Resisters' International's Right to Refuse to Kill programme is available at http://wri-irg.org/programmes/rrtk. News on WRI's work in relation to conscientious objection in Colombia can be found at http://wri-irg.org/campaigns/colombian_cos

2 See for example http://www.wri-irg.org/programmes/world_survey/reports/Colombia

3 See CO-Update No 29, May 2007, http://wri-irg.org/node/1116, and The Broken Rifle No 74, May 2007, http://wri-irg.org/pubs/br74-en.htm

4 See CO-Update No 52, November-December 2009, http://wri-irg.org/node/9188

5 Working Group on Arbitrary Detention: Opinion 8/2008 (Colombia), 8 May 2008, http://wri-irg.org/node/10513

6 See CO-Update No 58, August 2010, http://wri-irg.org/node/10676

7 See for example: Caracol Radio: Se pronuncia dirección de reclutamiento del Ejército, 3 October 2008, http://www.caracol.com.co/nota.aspx?id=683186, accessed 6 August 2010

8 See for example: El Tiempo, edicion Caribe: Pánico en Montería por extraño caso de reclutamiento de jóvenes por el Ejército, 26 November 2009, http://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/caribe/ARTICULO-PRINTER_FRIENDLY-PLANTILLA_PRINTER_FRIENDL-6681347.html, accessed 6 August 2010; See also: War Resisters' International: Military Recruitment and Conscientious objection in Colombia, Report to the Human Rights Committee, 97th Session, London, August 2009, http://wri-irg.org/node/8442

10 See http://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/comunicados/No.%2043%20Comunicado%2014%20de%20Octubre%20de%202009.php, accessed 10 August 2010

11 Andreas Speck: Implementación del derecho a la Objeción de Conciencia: Experiencias de la IRG, 2 June 2010, http://wri-irg.org/node/10569, accessed 10 August 2010

12Downloadable at http://fedescolombia.org/docs/Informe%20Falsos%20Positivos%20e%20Impunidad.%20FEDES.pdf

13Email Martin Rodriguez, 14 July 2010

15 According to the European Commission, the peace laboratories strategy implemented by the EU since 2002 supports local initiatives aimed at creating areas of peace, cohabitation, economic development and reconciliation. However, the regions chosen also point at strategic and economical interests. See: European Commission: COLOMBIA COUNTRY STRATEGY PAPER, 2007-2013, http://www.eeas.europa.eu/colombia/csp/07_13_en.pdf, accessed 6 August 2010

16 See for example: El Universal Sincelejo: Responsabilizan a autoridades del asesinato de líder, 20 May 2010, http://www.eluniversal.com.co/v2/print/45465, accessed 6 August 2010; El Tiempo: Ya son 45 los líderes de víctimas asesinados por reclamar sus tierras; en 15 días murieron tres, 2 June 2010, http://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/justicia/ARTICULO-PRINTER_FRIENDLY-PLANTILLA_PRINTER_FRIENDL-7737280.html, accessed 6 August 2010

17 PazCaribe: Cultura de Paz, http://pazcaribe.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=38&Itemid=56, accessed 10 August 2010

18 http://objecioncolombia.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=29&Itemid=54&lang=es

20 See http://wri-irg.org/node/2892 for more information on his case.

21 See Opinion No 8/2008 (Colombia), http://wri-irg.org/node/10513

22 http://objecioncolombia.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=24&Itemid=47&lang=es

23 http://www.redjuvenil.org. Red Juvenil is the only organisation in Colombia which is formally affiliated to War Resisters' International

Add new comment